Mbuti: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

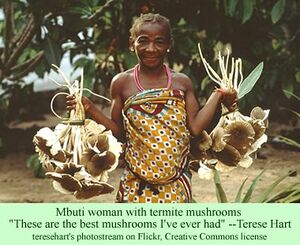

[[File:Mbuti woman with mushrooms1.jpg|thumbnail|Source: http://www.peacefulsocieties.org/Society/Mbuti.html]] | [[File:Mbuti woman with mushrooms1.jpg|thumbnail|Source: http://www.peacefulsocieties.org/Society/Mbuti.html]] | ||

The Mbuti hunter-gatherers in the Congo's Ituri Forest have traditionally lived in stateless communities with gift economies and largely egalitarian gender relations. The anthropologist Colin Turnbull, after living with a Mbuti band, remarked, "They were a people who had found in the forest something that made life more than just worth living, something that made it, with all its hardships and problems and tragedies, a wonderful thing full of joy and happiness and free of care."<ref>Colin Turbull, ''The Forest People'' (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1968) 28.</ref> Today, several thousands Mbuti live in the forest but face threats from the Congo's civil war and environmental devastation from coltan mining, deforestation and hunting.<ref>Peter Gelderloos, [[Anarchy Works]].</ref> | |||

=Culture= | |||

Mbuti culture trationally emphasized nearly egalitarian gender relations and extensive freedom for children. Men controlled the hunting, while women gathered vegetables and other foods.<ref>"Mbuti", ''Encyclopedia of Selected Peaceful Societies'', www.peacefulsocieties.org/Society/Mbuti.html.</ref> Peter Gelderloos, based on Turnbull's work, noted that the Mbuti do not have excessive distinction between genders: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

The Mbuti also discouraged competition or even excessive distinction between genders. They did not use gendered pronouns or familial words — e.g., instead of “son” they say “child,” “sibling” instead of “sister” — except in the case of parents, in which there is a functional difference between one who gives birth or provides milk and one who provides other forms of care. An important ritual game played by adult Mbuti worked to undermine gender competition. As Turnbull describes it, the game began like a tug-of-war match, with the women pulling one end of a long rope or vine and the men pulling the other. But as soon as one side started to win, someone from that team would run to the other side, also symbolically changing their gender and becoming a member of the other group. By the end, the participants collapsed in a heap laughing, all having changed their genders multiple times. Neither side “won,” but that seemed to be the point. Group harmony was restored.<ref>Gelderloos, [[Anarchy Works]].</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

However, Mbuti appeared to tolerate a degree of domestic abuse. Turnbull writes, that after a wedding ritual a woman is "told she is now her husband's responsibility and must fend for herself and not come running home every time she gets beaten."<ref>Turnbull, ''The Forest People'', 186.</ref> | |||

Children lived almost autonomously. In one game, around six children climbed a young tree, bending it to the ground. Then, they would all jump off, and anyone too slow would be flung into the air by the tree. Turnbull describes the life of Mbuti children as "one long frolic interspersed with a healthy sprinkle of spankings and slappings...And one day they find that the games they have been playing are not games any longer, but the real thing, for they have become adults. Their hunting is now real hunting; their climbing is in earnest search of innacessible honey; their acrobatics on the swings are repeated almost daily, in other forms, in the pursuit of elusive game, or in avoiding the malicious forest buffalo. It happens so gradually that they hardly notice the change at fist, for even when they are still proud and famous hunters their life is still full of fun and laughter."<ref>Turnbull, ''The Forest People,'' 129.</ref> | |||

=Decisions= | |||

Decisions are made in assemblies composed of the adult men and women. The Mbuti did not have a state, or chiefs or councils. Turnbull explains, "If you ask a Pygmy why his people have no chiefs, no lawmakers, no councils, or no leaders, he will answer with misleading simplicity, 'Because we are the people of the forest.' The forest, the great provider is the one standard by which all deeds and thoughts are judged; it is the chief, the lawgiver, the leader, and the final arbitrator."<ref>Turnbull, ''The Forest People'', 124-5.</ref> According to Gelderloos, ancient historians provided accounts of the Mbuti living as stateless hunter-gatherers during the reign of Egyptian pharohs, and the Mbuti themselves say they always lived that way.<ref>Gelderloos, [[Anarchy Works]].</ref> | |||

=Economy= | |||

As hunter-gatherers, the Mbuti practiced extensive mutual aid and gift-giving. Turnbull writes, "Hunting, for a Pygmy group, is a co-operative affair--net-hunting pharicularly."<ref>Turnbull, ''The Forest People'', 97.</ref> When a man caught and killed an animal, his wife would bring it back to the camp to share with others. Sometimes, people felt that food was distributed unfairly, and they would complain and squabble until the distribution was corrected.<ref><ref>"Mbuti", ''Encyclopedia of Selected Peaceful Societies'', www.peacefulsocieties.org/Society/Mbuti.html.</ref> The construction of temporay villages was also a communal affair. The Mbuti lived in mud huts about 7 feet by 5 feet.<ref>Turnbull, ''The Forest People'', 39, 59.</ref> | |||

Mbuti | =Environment= | ||

The Mbuti revered the forest and lived there sustainably for thousands of years. The Mbuti villager Moke told Turnbull, "The forest is a father and mother to us and like a father or mother it gives us everything we need--food, clothing, shelter, warmth...and affection."<ref>Turnbull, ''The Forest People'', 192.</ref> However, Turnbull describes their cruel treatment of animals, "I have seen the Pygmies sieging feathers off birds that were still alive, explaining that the meat is more tender if the death comes slowly. And the hunting dogs, valuable as they are, get kicked around mercilessly from the day they are born to the day they die.<ref>Turnbull, ''The Forest People'', 101.</ref> | |||

The Mbuti | =Crime= | ||

The Mbuti had several methods of punishing crime. For the less serious crimes, the parties themselves solved the matter, by "either arguing out the case, or engaging in a mild fight." For more serious crimes, the village's young men would sound an instrument mimicking an elephant and attack the criminal's hut. Villagers responded to very serious crimes with ostracism and threats of supernatural retribution.<ref>Turbull, ''The Forest People'', 110-111.</ref> Turnbull describes an instance where a hunger put his hunting net before others'. The camp responded by taunting and ridiculing him, refusing to give him a chair, and laughing at him. Eventually, he apologized and gave up the meat he had caught. Turnbull comments, "Cephu had committed what is probably one of the most serious crimes in Pygmy eyes, and one that rarely occurs. Yet the case was settled simply and effectively, without any evident legal system being brought into force. It cannot be said that Cephu went unpunished, because for those few hours when nobody would speak to him he must have suffered the equivalent of as many days solitary confinement for anyone else. To have been refused a chair by a mere youthm not even one fo the great hunters; to have been laughed at by women and children; to have been ignored by men--none of these things would be quickly forgotten. Without any formal process of law Cephu had been firmly put in his place, and it was unlikely he would do the same thing again in a hurry."<ref>Turnbull, ''The Forest People'', 104-110.</ref> In another instance, a man committed incest with his cousin, a very serious crime according to tradition. The youth chased him out of the village. After three days, he returned and the village accepted him back.<ref>Turbull, ''The Forest People'', 111-112.</ref> | |||

=Neighboring Societies= | |||

From Peter Gelderloos, Anarchy Works <ref>[[Anarchy Works]]</ref>: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

Contrary to common portrayals by outsiders, groups like the Mbuti are not isolated or primordial. In fact they have frequent interactions with the sedentary Bantu peoples surrounding the forest, and they have had plenty of opportunities to see what supposedly advanced societies are like. Going back at least hundreds of years, Mbuti have developed relationships of exchange and gift-giving with neighboring farmers, while retaining their identity as “the children of the forest.” | |||

Today several thousand Mbuti still live in the Ituri Forest and negotiate dynamic relationships with the changing world of the villagers, while fighting to preserve their traditional way of life. Many other Mbuti live in settlements along the new roads. Coltan mining for cell phones is a chief financial incentive for the civil war and the habitat destruction that is ravaging the region and killing hundreds of thousands of inhabitants. The governments of Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda all want to control this billion dollar industry, that produces primarily for the US and Europe, while miners seeking employment come from all over Africa to set up camp in the region. The deforestation, population boom, and increase in hunting to provide bush meat for the soldiers and miners have depleted local wildlife. Lacking food and competing for territorial control, soldiers and miners have taken to carrying out atrocities, including cannibalism, against the Mbuti. Some Mbuti are currently demanding an international tribunal against cannibalism and other violations. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

--[[User:DFischer|DFischer]] ([[User talk:DFischer|talk]]) 16:05, 22 October 2014 (EDT) | |||

Revision as of 13:05, 22 October 2014

The Mbuti hunter-gatherers in the Congo's Ituri Forest have traditionally lived in stateless communities with gift economies and largely egalitarian gender relations. The anthropologist Colin Turnbull, after living with a Mbuti band, remarked, "They were a people who had found in the forest something that made life more than just worth living, something that made it, with all its hardships and problems and tragedies, a wonderful thing full of joy and happiness and free of care."[1] Today, several thousands Mbuti live in the forest but face threats from the Congo's civil war and environmental devastation from coltan mining, deforestation and hunting.[2]

Culture

Mbuti culture trationally emphasized nearly egalitarian gender relations and extensive freedom for children. Men controlled the hunting, while women gathered vegetables and other foods.[3] Peter Gelderloos, based on Turnbull's work, noted that the Mbuti do not have excessive distinction between genders:

The Mbuti also discouraged competition or even excessive distinction between genders. They did not use gendered pronouns or familial words — e.g., instead of “son” they say “child,” “sibling” instead of “sister” — except in the case of parents, in which there is a functional difference between one who gives birth or provides milk and one who provides other forms of care. An important ritual game played by adult Mbuti worked to undermine gender competition. As Turnbull describes it, the game began like a tug-of-war match, with the women pulling one end of a long rope or vine and the men pulling the other. But as soon as one side started to win, someone from that team would run to the other side, also symbolically changing their gender and becoming a member of the other group. By the end, the participants collapsed in a heap laughing, all having changed their genders multiple times. Neither side “won,” but that seemed to be the point. Group harmony was restored.[4]

However, Mbuti appeared to tolerate a degree of domestic abuse. Turnbull writes, that after a wedding ritual a woman is "told she is now her husband's responsibility and must fend for herself and not come running home every time she gets beaten."[5]

Children lived almost autonomously. In one game, around six children climbed a young tree, bending it to the ground. Then, they would all jump off, and anyone too slow would be flung into the air by the tree. Turnbull describes the life of Mbuti children as "one long frolic interspersed with a healthy sprinkle of spankings and slappings...And one day they find that the games they have been playing are not games any longer, but the real thing, for they have become adults. Their hunting is now real hunting; their climbing is in earnest search of innacessible honey; their acrobatics on the swings are repeated almost daily, in other forms, in the pursuit of elusive game, or in avoiding the malicious forest buffalo. It happens so gradually that they hardly notice the change at fist, for even when they are still proud and famous hunters their life is still full of fun and laughter."[6]

Decisions

Decisions are made in assemblies composed of the adult men and women. The Mbuti did not have a state, or chiefs or councils. Turnbull explains, "If you ask a Pygmy why his people have no chiefs, no lawmakers, no councils, or no leaders, he will answer with misleading simplicity, 'Because we are the people of the forest.' The forest, the great provider is the one standard by which all deeds and thoughts are judged; it is the chief, the lawgiver, the leader, and the final arbitrator."[7] According to Gelderloos, ancient historians provided accounts of the Mbuti living as stateless hunter-gatherers during the reign of Egyptian pharohs, and the Mbuti themselves say they always lived that way.[8]

Economy

As hunter-gatherers, the Mbuti practiced extensive mutual aid and gift-giving. Turnbull writes, "Hunting, for a Pygmy group, is a co-operative affair--net-hunting pharicularly."[9] When a man caught and killed an animal, his wife would bring it back to the camp to share with others. Sometimes, people felt that food was distributed unfairly, and they would complain and squabble until the distribution was corrected.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag The construction of temporay villages was also a communal affair. The Mbuti lived in mud huts about 7 feet by 5 feet.[10]

Environment

The Mbuti revered the forest and lived there sustainably for thousands of years. The Mbuti villager Moke told Turnbull, "The forest is a father and mother to us and like a father or mother it gives us everything we need--food, clothing, shelter, warmth...and affection."[11] However, Turnbull describes their cruel treatment of animals, "I have seen the Pygmies sieging feathers off birds that were still alive, explaining that the meat is more tender if the death comes slowly. And the hunting dogs, valuable as they are, get kicked around mercilessly from the day they are born to the day they die.[12]

Crime

The Mbuti had several methods of punishing crime. For the less serious crimes, the parties themselves solved the matter, by "either arguing out the case, or engaging in a mild fight." For more serious crimes, the village's young men would sound an instrument mimicking an elephant and attack the criminal's hut. Villagers responded to very serious crimes with ostracism and threats of supernatural retribution.[13] Turnbull describes an instance where a hunger put his hunting net before others'. The camp responded by taunting and ridiculing him, refusing to give him a chair, and laughing at him. Eventually, he apologized and gave up the meat he had caught. Turnbull comments, "Cephu had committed what is probably one of the most serious crimes in Pygmy eyes, and one that rarely occurs. Yet the case was settled simply and effectively, without any evident legal system being brought into force. It cannot be said that Cephu went unpunished, because for those few hours when nobody would speak to him he must have suffered the equivalent of as many days solitary confinement for anyone else. To have been refused a chair by a mere youthm not even one fo the great hunters; to have been laughed at by women and children; to have been ignored by men--none of these things would be quickly forgotten. Without any formal process of law Cephu had been firmly put in his place, and it was unlikely he would do the same thing again in a hurry."[14] In another instance, a man committed incest with his cousin, a very serious crime according to tradition. The youth chased him out of the village. After three days, he returned and the village accepted him back.[15]

Neighboring Societies

From Peter Gelderloos, Anarchy Works [16]:

Contrary to common portrayals by outsiders, groups like the Mbuti are not isolated or primordial. In fact they have frequent interactions with the sedentary Bantu peoples surrounding the forest, and they have had plenty of opportunities to see what supposedly advanced societies are like. Going back at least hundreds of years, Mbuti have developed relationships of exchange and gift-giving with neighboring farmers, while retaining their identity as “the children of the forest.”

Today several thousand Mbuti still live in the Ituri Forest and negotiate dynamic relationships with the changing world of the villagers, while fighting to preserve their traditional way of life. Many other Mbuti live in settlements along the new roads. Coltan mining for cell phones is a chief financial incentive for the civil war and the habitat destruction that is ravaging the region and killing hundreds of thousands of inhabitants. The governments of Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda all want to control this billion dollar industry, that produces primarily for the US and Europe, while miners seeking employment come from all over Africa to set up camp in the region. The deforestation, population boom, and increase in hunting to provide bush meat for the soldiers and miners have depleted local wildlife. Lacking food and competing for territorial control, soldiers and miners have taken to carrying out atrocities, including cannibalism, against the Mbuti. Some Mbuti are currently demanding an international tribunal against cannibalism and other violations.

- ↑ Colin Turbull, The Forest People (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1968) 28.

- ↑ Peter Gelderloos, Anarchy Works.

- ↑ "Mbuti", Encyclopedia of Selected Peaceful Societies, www.peacefulsocieties.org/Society/Mbuti.html.

- ↑ Gelderloos, Anarchy Works.

- ↑ Turnbull, The Forest People, 186.

- ↑ Turnbull, The Forest People, 129.

- ↑ Turnbull, The Forest People, 124-5.

- ↑ Gelderloos, Anarchy Works.

- ↑ Turnbull, The Forest People, 97.

- ↑ Turnbull, The Forest People, 39, 59.

- ↑ Turnbull, The Forest People, 192.

- ↑ Turnbull, The Forest People, 101.

- ↑ Turbull, The Forest People, 110-111.

- ↑ Turnbull, The Forest People, 104-110.

- ↑ Turbull, The Forest People, 111-112.

- ↑ Anarchy Works