Paris Commune: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "File:640px-Barricade Paris 1871 by Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg.jpg|thumbnail| A barricade constructed by the Commune in April 1871 on the Rue de Rivoli near the Hotel de Ville...") |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

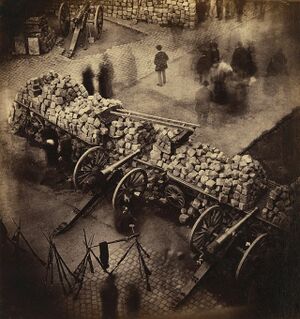

[[File:640px-Barricade Paris 1871 by Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg.jpg|thumbnail| A barricade constructed by the Commune in April 1871 on the Rue de Rivoli near the Hotel de Ville. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_Commune]] | [[File:640px-Barricade Paris 1871 by Pierre-Ambrose Richebourg.jpg|thumbnail| A barricade constructed by the Commune in April 1871 on the Rue de Rivoli near the Hotel de Ville. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_Commune]] | ||

From 18 March to 28 May 1871, the two million residents of Paris ran their city as an autonomous commune, established forty-three worker cooperatives, and advocated for a federation of revolutionary communes across France. With anarchists' participation, the mass uprising and social reforms of the Commune briefly moved moved Paris in a sharply anarchistic direction. “Under the name of the ''Paris Commune'' a new ''idea'' was born, to become the starting point for future revolutions,” Peter Kropotkin later enthused.<ref>Peter Kropotkin, “The Paris Commune” in ed. Iain McKay, ''Direct Struggle Against Capital: A Peter Kropotkin Anthology'' (Oakland: AK Press, 2014), 440.</ref> | |||

The | Anarchists argue that the main problem with the Paris Commune was that it did not go far enough in its social revolution. Although it declared itself autonomous from the French state, it did not abolish statist structures internally. And although it implemented a number of economic reforms, it did not expropriate capital or try to abolish wage labor. Consequently, the Parisian masses lost much of their enthusiasm by the time the French army came to destroy it. Kropotkin reflected: | ||

<blockquote> | |||

As if there were any way of defeating the enemy so long as the great mass of the people is not directly interested in the triumph of the revolution by seeing that it will bring material, intellectual, and moral well-being for everyone! They tried to consolidate the Commune first and put off the social revolution until later, whereas the only way to proceed was to ''consolidate the Commune by means of the social revolution!''<ref>Kropotkin, “The Paris Commune,” 445.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

Another major mistake, according to Friedrich Engels, was that the Communards did not seize Paris's Bank of France, which “would have been worth more than ten thousand hostages”.<ref>Engels, Introduction to ''The Civil War in France'' in ed. Robert C. Tucker, ''The Marx-Engels Reader'' (New York: Princeton University, 1972), 626.</ref> The bank's vaults held all of France's gold.<ref>Harman, ''A People's History of the World'' (New York: Verso, 2008), 373.</ref> | |||

In May, the French army invaded Paris and shot Communard who resisted on the spot. The army killed 200,000 to 300,000 Communards and imprisoned another 40,000.<ref>Chris Harman, ''A People's History of the World: From the Stone Age to the New Millennium'' (New York: Verso, 2008), 373-374.</ref> | |||

=Background= | |||

In July 1870, “Louis Bonaparte allowed the Prussian leader Bismarck to provoke him into declaring war.”<ref>Harman, ''A People's History of the World'', 369.</ref> | |||

Even after Prussia invaded Paris, the Parisians kept fighting in defense in their city. Five months later, the French government surrendered, causing Parisians to feel extremely betrayed “They had suffered five months for nothing.”<ref>Harman, ''A People's History of the World'', 370.</ref> On 18 March 1871, the newly-appointed French president August Theirs sent soldiers into Paris to seize canons from the National Guard, which was controlled by the Parisian masses. | |||

Kropotkin wrote in “Commune in Paris” that the uprising had three periods: a week of popular uprising leading to the elections, the two months of the Commune, and the last week of popular defense. “During the first and last we see the ''people'' at work. The middle is a period of Parliamentary government.”<ref>Kropotkin, “Commune of Paris” in ''Direct Struggle Against Capital'', 451.</ref> | |||

=Initial Uprising= | |||

Masses of Parisians resisted the French army's attempt on 18 March 1871 to seize canons from the Parisian National Guard. According to one eyewitness account, soldiers could not reach the canons because “waves of people engulfed everything.”<ref>”An eyewitness account” in ed. Stewart Edwards, ''The Communards of Paris'' (London: Thames and Hudson, 1973), 62.</ref> Women surrounding soldiers on horses cried out, “Unharness the horses!”. Rebels lifted soldiers off the horses, and the crowd cheered as they let the freed horses walk through. Parisians offered wine and meat to the hungry French soldiers. “They were soon won over to the side of the rebels,” the eyewitness reported.<ref>”An eyewitness account” in ''The Communards of Paris'', 63.</ref> When General Lecomte ordered soldiers to fire at a crowd of women and children, the soldiers refused and instead seized the general.<ref>Edwards, ''The Communards of Paris'', 64.</ref> | |||

The national army withdrew later that day. The Parisian National Guard occupied the city hall, declared Paris autonomous from France, and called for elections on 26 March to elect a 92-member governing council.<ref>Robert Graham, ''We Do Not Fear Anarchy, We Invoke It: The First International and the Origins of the Anarchist Movement'' (Oakland: AK Press, 2015), 146.</ref> The hope was that communes would spring up over the rest of France and join together in a revolutionary confederation. | |||

“The first week is a period of great enthusiasm,” wrote Kropotkin. “The Government is overthrown. Paris is free...The greatest hopes are roused in the downtrodden masses by the new conditions. It is a ''popular movement'', without orders from above, without direction.”<ref>Kropotkin, “Commune of Paris,” 451.</ref> | |||

=Communal Governance= | |||

Parisians voted on 26 March. Two days later, at the Hotel de Ville, the National Guard formally established the Paris Commune. Most of the council members were Jacobins and Blanquists (authoritarian socialists), and a small minority were Proudhonists.<ref>ed. Edwards, ''The Communards of Paris'', 26-27. Graham, ''We Do Not Fear Anarchy: We Invoke It'', 146-147.</ref> | |||

Council members could be immediately recalled by the electorate, and they received only an average wage. The effect, as Friedrich Engels explained, was to prevent a class of unaccountable politicians from arising: “In this way an effective barrier to place-hunting and careerism was set up, even apart from the binding mandates to delegates to representative bodies which were added besides.”<ref>Frederich Engels, Introduction to ''The Civil War in France'', in ''Marx-Engels Reader'', 628.</ref> Staying within the convention of the time, the Commune did not extend suffrage to women.<ref>Harman, ''A People's History of the World'' 373-4.</ref> | |||

The Commune abolished night work for bakers, prohibited employers from making their workers pay fines, and required owners of closed factories to hand over the buildings to workers to be reopened as cooperatives.<ref>Karl Marx, excerpts from ''The Civil War in France'' in ''The Marx-Engels Reader'', 639.</ref> In total, the Commune set up forty-three worker cooperatives.<ref>”A.5.1. The Paris Commune” in [[An Anarchist FAQ]].</ref> The Commune also opened up several schools, including one for women.<ref>Edwards, ''The Communards of Paris'', 37.</ref> | |||

Kropotkin later argued that the Commune did not go far enough in abolishing hierarchy in either decision-making or in the economy. Aside from attempting to keep out career politicians, the council was not otherwise different from a regular parliamentary government. And while the Commune set up new worker cooperatives without bosses, it did not get rid of existing bosses. There was no expropriation of capital or elimination of wage labor. “The months of Communal rule are the dullest, most unproductive months in revolutionary history. Not one single great idea coming to the front,” Kropotkin argued.<ref>Kropotkin, “Commune of Paris”, 453.</ref> | |||

Outside of the council, however, Parisians organized many popular clubs and organizations that practiced direct democracy at the neighborhood level. The artist Gustave Courbet described Paris as “a true paradise...all social groups have established themselves as federations and are masters of their own fate”.<ref>”A.5.1. The Paris Commune” in [[An Anarchist FAQ]].</ref> Clubs often disseminated ideas that were far more radical than those of council. At a women's club, a Communard railed against marriage: “Marriage, ''citoyennes'', is the greatest error of ancient humanity. To be married is to be a slave. Will you be slaves?”<ref>”Speech made in a women's club,” ''The Communards of Paris'', 108.</ref> | |||

Crime was virtually absent in the Commune. A Communard reported, “We hear no longer of assassination, theft and personal assault”.<ref>Marx, excerpts from ''The Civil War in France'' in ''Marx-Engels Reader'', 641.</ref> The city had a festive atmosphere. “Would you believe it?,” asked Villiers de l'Isle-Adam. “Paris is fighting and singing...Paris does not only have soldiers, she has singers too. She has both cannons and violins; she makes both Orsini bombs and music. The clash of cymbals can be heard in the dreadful silence between rounds of firing, and merry dance airs mingle with the rattle of American machine-guns.”<ref>“Paris as festival” in ''The Communards of Paris'', 140.</ref> | |||

Proudhonists and other anarchists opposed the Commune's establishment of a Committee of Public Safety to defend the city. Named after the Jacobins' terroristic body in the 1789 French Revolution, this Committee raised enough alarms that a minority of the council resigned. “By a special and explicit vote the Paris Commune has surrendered its authority to a dictatorship,” the minority declaration stated.<ref>“The minority declaration” in ''The Communards of Paris'', 93.</ref> | |||

=The last week= | |||

The French army started attacking Paris again on 2 April. On 21 May, troops entered Paris and fought Communards on the streets for the next week, until the Commune fell.<ref>''The Communards of Paris'', 30, 40.</ref> | |||

Parisians had called upon the rest of the country to rise up, and for a confederation of autonomous communes to replace the French nation-state. This did not happen. As a result, the Commune was bound to fall sooner or later. “The defeat of the Commune was certain,” explained Kropotkin.<ref>Kropotkin, “The Paris Commune,” 453.</ref> Kropotkin insisted, however, that the Commune may have held up better if the masses had been more actively involved in the revolution. He acknowledged in the last week the masses launched an extremely courageous defense: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

This was, again, the ''people'' of Paris in their desperate battle against the middle classes, and were it not for this fight, unorganised, free, full of personal initiative and heroism, without chiefs and without gold-embroidered caps, we should never have come together to commemorate that Revolution”.<ref>Kropotkin, “The Commune of Paris,” 454.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

=Marx and the Paris Commune= | |||

Despite calling the Franco-Prussian War a “fratricidal feud”<ref>Karl Marx, “First Address of the General Council on the Franco-Prussian War” in Karl Marx and V.I. Lenin, ''Civil War in France: The Paris Commune'', (New York: International Publishers, 1968), 27</ref> in a public address, Karl Marx supported the war in a letter to German Social Democrats. He figured that the war would hurt anarchist trends and help his brand of socialism gain influence . He reasoned, “The French need to be overcome...the ascendancy of the German proletariat over the French proletariat will at the same time constitute the ascendancy of ''our'' theory over Proudhon's.”<ref>Graham, ''We Do Not Fear Anarchy: We Invoke It'', 140.</ref> | |||

The Paris Commune reflected anarchist ideas of community control, worker association, and confederation. Surprisingly, therefore, Marx strongly embraced the Commune and his writing on it contains many libertarian passages. | |||

<blockquote> | |||

But the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes. | |||

The centralised State power, with its ubiquitous organs of standing army, police, bureaucracy, clergy, and judicature—organs wrought after the plan of a systematic and hierarchic division of labour,--originates from the days of absolute monarchy<ref>Marx, excerpts from ''The Civil War in France'', in ''The Marx-Engels Reader'', 629.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

According to Stewart Edwards, the reflection on the Paris Commune “was about as close to anarchism as the mature Marx ever came.”<ref>''The Communards of Paris'', 10.</ref> | |||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 18:08, 14 January 2016

From 18 March to 28 May 1871, the two million residents of Paris ran their city as an autonomous commune, established forty-three worker cooperatives, and advocated for a federation of revolutionary communes across France. With anarchists' participation, the mass uprising and social reforms of the Commune briefly moved moved Paris in a sharply anarchistic direction. “Under the name of the Paris Commune a new idea was born, to become the starting point for future revolutions,” Peter Kropotkin later enthused.[1]

Anarchists argue that the main problem with the Paris Commune was that it did not go far enough in its social revolution. Although it declared itself autonomous from the French state, it did not abolish statist structures internally. And although it implemented a number of economic reforms, it did not expropriate capital or try to abolish wage labor. Consequently, the Parisian masses lost much of their enthusiasm by the time the French army came to destroy it. Kropotkin reflected:

As if there were any way of defeating the enemy so long as the great mass of the people is not directly interested in the triumph of the revolution by seeing that it will bring material, intellectual, and moral well-being for everyone! They tried to consolidate the Commune first and put off the social revolution until later, whereas the only way to proceed was to consolidate the Commune by means of the social revolution![2]

Another major mistake, according to Friedrich Engels, was that the Communards did not seize Paris's Bank of France, which “would have been worth more than ten thousand hostages”.[3] The bank's vaults held all of France's gold.[4]

In May, the French army invaded Paris and shot Communard who resisted on the spot. The army killed 200,000 to 300,000 Communards and imprisoned another 40,000.[5]

Background

In July 1870, “Louis Bonaparte allowed the Prussian leader Bismarck to provoke him into declaring war.”[6]

Even after Prussia invaded Paris, the Parisians kept fighting in defense in their city. Five months later, the French government surrendered, causing Parisians to feel extremely betrayed “They had suffered five months for nothing.”[7] On 18 March 1871, the newly-appointed French president August Theirs sent soldiers into Paris to seize canons from the National Guard, which was controlled by the Parisian masses.

Kropotkin wrote in “Commune in Paris” that the uprising had three periods: a week of popular uprising leading to the elections, the two months of the Commune, and the last week of popular defense. “During the first and last we see the people at work. The middle is a period of Parliamentary government.”[8]

Initial Uprising

Masses of Parisians resisted the French army's attempt on 18 March 1871 to seize canons from the Parisian National Guard. According to one eyewitness account, soldiers could not reach the canons because “waves of people engulfed everything.”[9] Women surrounding soldiers on horses cried out, “Unharness the horses!”. Rebels lifted soldiers off the horses, and the crowd cheered as they let the freed horses walk through. Parisians offered wine and meat to the hungry French soldiers. “They were soon won over to the side of the rebels,” the eyewitness reported.[10] When General Lecomte ordered soldiers to fire at a crowd of women and children, the soldiers refused and instead seized the general.[11]

The national army withdrew later that day. The Parisian National Guard occupied the city hall, declared Paris autonomous from France, and called for elections on 26 March to elect a 92-member governing council.[12] The hope was that communes would spring up over the rest of France and join together in a revolutionary confederation.

“The first week is a period of great enthusiasm,” wrote Kropotkin. “The Government is overthrown. Paris is free...The greatest hopes are roused in the downtrodden masses by the new conditions. It is a popular movement, without orders from above, without direction.”[13]

Communal Governance

Parisians voted on 26 March. Two days later, at the Hotel de Ville, the National Guard formally established the Paris Commune. Most of the council members were Jacobins and Blanquists (authoritarian socialists), and a small minority were Proudhonists.[14]

Council members could be immediately recalled by the electorate, and they received only an average wage. The effect, as Friedrich Engels explained, was to prevent a class of unaccountable politicians from arising: “In this way an effective barrier to place-hunting and careerism was set up, even apart from the binding mandates to delegates to representative bodies which were added besides.”[15] Staying within the convention of the time, the Commune did not extend suffrage to women.[16]

The Commune abolished night work for bakers, prohibited employers from making their workers pay fines, and required owners of closed factories to hand over the buildings to workers to be reopened as cooperatives.[17] In total, the Commune set up forty-three worker cooperatives.[18] The Commune also opened up several schools, including one for women.[19]

Kropotkin later argued that the Commune did not go far enough in abolishing hierarchy in either decision-making or in the economy. Aside from attempting to keep out career politicians, the council was not otherwise different from a regular parliamentary government. And while the Commune set up new worker cooperatives without bosses, it did not get rid of existing bosses. There was no expropriation of capital or elimination of wage labor. “The months of Communal rule are the dullest, most unproductive months in revolutionary history. Not one single great idea coming to the front,” Kropotkin argued.[20]

Outside of the council, however, Parisians organized many popular clubs and organizations that practiced direct democracy at the neighborhood level. The artist Gustave Courbet described Paris as “a true paradise...all social groups have established themselves as federations and are masters of their own fate”.[21] Clubs often disseminated ideas that were far more radical than those of council. At a women's club, a Communard railed against marriage: “Marriage, citoyennes, is the greatest error of ancient humanity. To be married is to be a slave. Will you be slaves?”[22]

Crime was virtually absent in the Commune. A Communard reported, “We hear no longer of assassination, theft and personal assault”.[23] The city had a festive atmosphere. “Would you believe it?,” asked Villiers de l'Isle-Adam. “Paris is fighting and singing...Paris does not only have soldiers, she has singers too. She has both cannons and violins; she makes both Orsini bombs and music. The clash of cymbals can be heard in the dreadful silence between rounds of firing, and merry dance airs mingle with the rattle of American machine-guns.”[24]

Proudhonists and other anarchists opposed the Commune's establishment of a Committee of Public Safety to defend the city. Named after the Jacobins' terroristic body in the 1789 French Revolution, this Committee raised enough alarms that a minority of the council resigned. “By a special and explicit vote the Paris Commune has surrendered its authority to a dictatorship,” the minority declaration stated.[25]

The last week

The French army started attacking Paris again on 2 April. On 21 May, troops entered Paris and fought Communards on the streets for the next week, until the Commune fell.[26]

Parisians had called upon the rest of the country to rise up, and for a confederation of autonomous communes to replace the French nation-state. This did not happen. As a result, the Commune was bound to fall sooner or later. “The defeat of the Commune was certain,” explained Kropotkin.[27] Kropotkin insisted, however, that the Commune may have held up better if the masses had been more actively involved in the revolution. He acknowledged in the last week the masses launched an extremely courageous defense:

This was, again, the people of Paris in their desperate battle against the middle classes, and were it not for this fight, unorganised, free, full of personal initiative and heroism, without chiefs and without gold-embroidered caps, we should never have come together to commemorate that Revolution”.[28]

Marx and the Paris Commune

Despite calling the Franco-Prussian War a “fratricidal feud”[29] in a public address, Karl Marx supported the war in a letter to German Social Democrats. He figured that the war would hurt anarchist trends and help his brand of socialism gain influence . He reasoned, “The French need to be overcome...the ascendancy of the German proletariat over the French proletariat will at the same time constitute the ascendancy of our theory over Proudhon's.”[30]

The Paris Commune reflected anarchist ideas of community control, worker association, and confederation. Surprisingly, therefore, Marx strongly embraced the Commune and his writing on it contains many libertarian passages.

But the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery, and wield it for its own purposes. The centralised State power, with its ubiquitous organs of standing army, police, bureaucracy, clergy, and judicature—organs wrought after the plan of a systematic and hierarchic division of labour,--originates from the days of absolute monarchy[31]

According to Stewart Edwards, the reflection on the Paris Commune “was about as close to anarchism as the mature Marx ever came.”[32]

- ↑ Peter Kropotkin, “The Paris Commune” in ed. Iain McKay, Direct Struggle Against Capital: A Peter Kropotkin Anthology (Oakland: AK Press, 2014), 440.

- ↑ Kropotkin, “The Paris Commune,” 445.

- ↑ Engels, Introduction to The Civil War in France in ed. Robert C. Tucker, The Marx-Engels Reader (New York: Princeton University, 1972), 626.

- ↑ Harman, A People's History of the World (New York: Verso, 2008), 373.

- ↑ Chris Harman, A People's History of the World: From the Stone Age to the New Millennium (New York: Verso, 2008), 373-374.

- ↑ Harman, A People's History of the World, 369.

- ↑ Harman, A People's History of the World, 370.

- ↑ Kropotkin, “Commune of Paris” in Direct Struggle Against Capital, 451.

- ↑ ”An eyewitness account” in ed. Stewart Edwards, The Communards of Paris (London: Thames and Hudson, 1973), 62.

- ↑ ”An eyewitness account” in The Communards of Paris, 63.

- ↑ Edwards, The Communards of Paris, 64.

- ↑ Robert Graham, We Do Not Fear Anarchy, We Invoke It: The First International and the Origins of the Anarchist Movement (Oakland: AK Press, 2015), 146.

- ↑ Kropotkin, “Commune of Paris,” 451.

- ↑ ed. Edwards, The Communards of Paris, 26-27. Graham, We Do Not Fear Anarchy: We Invoke It, 146-147.

- ↑ Frederich Engels, Introduction to The Civil War in France, in Marx-Engels Reader, 628.

- ↑ Harman, A People's History of the World 373-4.

- ↑ Karl Marx, excerpts from The Civil War in France in The Marx-Engels Reader, 639.

- ↑ ”A.5.1. The Paris Commune” in An Anarchist FAQ.

- ↑ Edwards, The Communards of Paris, 37.

- ↑ Kropotkin, “Commune of Paris”, 453.

- ↑ ”A.5.1. The Paris Commune” in An Anarchist FAQ.

- ↑ ”Speech made in a women's club,” The Communards of Paris, 108.

- ↑ Marx, excerpts from The Civil War in France in Marx-Engels Reader, 641.

- ↑ “Paris as festival” in The Communards of Paris, 140.

- ↑ “The minority declaration” in The Communards of Paris, 93.

- ↑ The Communards of Paris, 30, 40.

- ↑ Kropotkin, “The Paris Commune,” 453.

- ↑ Kropotkin, “The Commune of Paris,” 454.

- ↑ Karl Marx, “First Address of the General Council on the Franco-Prussian War” in Karl Marx and V.I. Lenin, Civil War in France: The Paris Commune, (New York: International Publishers, 1968), 27

- ↑ Graham, We Do Not Fear Anarchy: We Invoke It, 140.

- ↑ Marx, excerpts from The Civil War in France, in The Marx-Engels Reader, 629.

- ↑ The Communards of Paris, 10.