Revolutionary Spain: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

committees in all “republican” -held cities. Although workers control existed | committees in all “republican” -held cities. Although workers control existed | ||

in theory, it had virtually disappeared in fact.<ref>Bookchin, "To Remember Spain." | in theory, it had virtually disappeared in fact.<ref>Bookchin, "To Remember Spain." | ||

</ | </blockquote> | ||

Revision as of 13:29, 1 January 2018

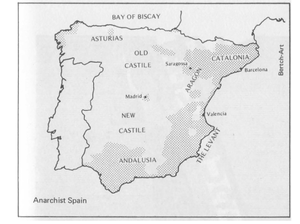

During the 1936-9 Spanish Civil War, anarchists coordinated thousands of horizontally-run communities, factories and farms, especially in the regions of Catalonia, Aragon, and the Levant. Frank Mintz estimates that the anarchist collectives encompassed 610,000 to 800,000 workers, or 3,200,000 people including their families. Gaston Leval, a French anarchist who fought in the war, describes a "revolutionary experience involving, directly or indirectly, 7 to 8 million people."[1].

The 1.5 million-member anarcho-syndicalist National Confederation of Labor (CNT) and the 300,000-member Anarchist Federation of Iberia (FAI) coordinated the anarchist collectives and organized militias to defend them. Because of their close collaboration, writers often abbreviate the two organizations together as CNT-FAI.

The Spanish Civil War pitted Fransisco Franco's fascists against an alliance of anarchists, Communists, Socialists and Republicans. Within the anti-fascist side, anarchists faced severe repression from the Communists and Republicans; in May of 1937, the Communists attacked anarchists in Barcelona, sounding "the death-knell of the revolution” according to Broué and Témime.[2] However, collectives retained various degrees of power throughout the civil war, and Sam Dolgoff refers to “the Spanish Revolution of 1936-1939.”[3]

Culture

The journalist George Orwell, who fought in the civil war with the Marxist POUM militia, describes anarchist-held Catalonia in 1936 as a site of a far-reaching cultural transformation:

It was the first time I had ever been in a town where the working class was in the saddle. Practically every building of any seized by the workers and was draped with red flags or with the red and black flag of the Anarchists; every wall was scrawled with the hammer and sickle and with the initials of the revolutionary parties; almost every church had been gutted and its images burnt. Churches here and there were being systematically demolished by gangs of workmen. Every shop and café had an inscription saying that it had been collectivized; even the bootblacks had been collectivized and their boxes painted red and black. Waiters and shop-walkers looked you in the face and treated you as an equal. Servile and even ceremonial forms of speech had temporarily disappeared. Nobody said 'Señor' or 'Don' or even 'Usted'; everyone called everyone else 'Comrade' and 'Thou,' and said 'Salud!' instead of 'Buenos dias.' Tipping had been forbidden by law since the time of Primo de Rivera; almost my first experience was receiving a lecture from an hotel manager for trying to tip a lift-boy. There were no private motor cars, they had all been commandered, and all the trams and taxis and much of the other transport were painted red and black. The revolutionary posters were everywhere, flaming from the walls in clean reds and blues that made the few remaining advertisements look like daubs of mud. Down the Ramblas, the wide central artery of the town where crowds of people streamed constantly to and fro, the loud-speakers were bellowing revolutionary songs all day and far into the night. And it was the aspect of the crowds that was the queerest thing of all. In outward appearance it was a town in which the wealthy classes had practically ceased to exist. Except for a small number of women and foreigners there were no 'well-dressed' people at all. Practically everyone wore rough working-class clothes, or blue overalls or some variant of the militia uniform. All this was queer and moving. There was much in it that I did not understand, in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for.”[4]

Anarchist women recognized and collectively confronted sexism within the revolution. Azucena Fernandez Barba recounts that in Barcelona, men would talk about revolution outside of the household and then act as masters within the household: "They struggled, they went on strike, etc. But inside the house, worse than nothing. I think we should have set an example with our own lives, lived differently in accordance with what we said we wanted. But no, [for them] the struggle was outside. Inside the house, [our desires] were purely utopian."[5]

In May 1936, anarchist women formed the group Mujeres Libres, meaning “Free Women,” advocating an end to sexism and all other forms of domination. They struggled for rights to contraception, abortion and divorce. Membership rose to 30,000 over the two years of the group's existence. They established a women's college in Barcelona, maternity hospitals, and schools for children. Women initially fought in the anarchist militias, but the Republican government ordered women to leave the frontlines in November of 1936.[6] An important contribution of Mujeres Libres, Martha A. Ackelsberg argues, was the refusal to treat the struggle against sexism as reducible to or subordinate to class struggle. Instead, they "recognized various types of subordination (e.g., political and sexual, as well as economic) as more or less independent relationships, each of which would need to be addressed by a truly revolutionary movement."[7]

Peter Marshall describes some limitations of women's liberation in revolutionary Spain:

The liberation of women, however, was only partial: they were often paid a lower rate than men in the collective; they continued to perform 'women's work'; they saw the struggle primarily in terms of class and not sex. But in a traditionally Catholic and patriarchal society, there were undoubtedly new possibilities for women and they appeared unaccompanied in public for the first time with a new self-assurance. [8]

In its 1936 Saragossa program, the anarcho-syndicalist CNT agreed to support and send supplies to people with a broad variety of lifestyles, including those who wished to live as naturalists, nudists and non-industrialists. Daniel Guérin comments, “Does this make us smile? On the eve of a vast, blood, social transformation, the CNT did not think it foolish to try to meet the infinitely varied aspirations of individual human beings.”[9]

Decisions

Aragon

In rural Aragon, collectivized towns implemented what Gaston Leval calls “libertarian democracy,” based on majority vote. Local decision-making assemblies met weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly depending on the town. Leval remarked that these assemblies “would not last more than a few hours. They dealt with concrete, precise subjects concretely and precisely. And all who had something to say could express themselves.”

Leval describes an assembly he attended in Huesca, Aragon. About 500 people attended, including 100 women. One agenda item involved residents who had left the collective. These “individualists” needed bread and wanted to take one of the collective's bakeries for themselves. After discussing several possible responses, the town assembly decided to keep the bakery but to bake extra bread for the individualists, on the condition that they supplied their own flour. [10]

Catalonia

The Republican government of industrial Catalonia effectively collapsed in July 1936, when the anarchists successfully defended the region from Franco's attack. After the battle, the CNT-FAI “seized post offices and telephone exchanges, formed police squads and militia units in Barcelona and in other towns and villages of Catalonia, and through their dominion over most of the economic life in the region.” The liberal historian Burnett Bolloten writes that the “practical significance” of the Catalan government “all but disappeared in the whirlwind of the Revolution.”[11] Chomsky concurs, “In Catalonia, the bourgeois government headed by Luis Companys retained nominal authority, but real power was in the hands of the anarchist-dominated communities.”[12]

Catalonia's president Luis Companys convinced the anarchists to establish the independent but proto-statist Central Anti-Fascist Militia Committee, which included representatives from the anarchist groups and other anti-fascists. According to the Bolloten, the Committee “immediately became the de facto executive body in the region. Its power rested not on the shattered machinery of state but on the revolutionary milita and police squads and upon the multitudinous committees that sprang up in the region during the first days of the Revolution.”[13] Tom Wetzel argues that the Central Anti-Fascist Militia Committee “was not an organ of working class 'dual power.' The Popular Front leaders in fact controlled the committee, just like the government.” Of the committee's 15 seats, the CNT and FAI together only held five. Although the CNT had three times the Socialist UGT's membership, both organizations had 3 seats.[14]

FAI

The Anarchist Federation of Iberia (FAI) “formed a near-model of libertarian organization,” according to Murray Bookchin. Its basic political unit was the affinity group:

Affinity groups were small nuclei of intimate friends which generally numbered a dozen or so men and women. Wherever several of these affinity groups existed, they were coordinated by a local federation and met, when possible, in monthly assemblies. The national movement, in turn, was coordinated by a Peninsular Committee, which ostensibly exercised very little directive power. Its role was meant to be strictly administrative in typical Bakuninist fashion. Affinity groups were in fact remarkably autonomous during the early thirties and often exhibited exceptional initiative. [15]

Over time, however, the FAI's Peninsular Committee, despite the non-binding quality of its recommendations, started to be increasingly treated as a traditional coordinating body. Bookchin observes, "the FAI increasingly became an end in itself and loyalty to the organization, particularly when it was under attack or confronted with severe difficulties, tended to mute criticism."[16]

Economy

The Spanish collectives initially practiced “mutualism”, a form of market socialism involving the abolition of wage-labor (working for bosses) but not the wage system.[17] Various industries formed federations to coordinate their activities without relying on the market, and some localities formed collectivist and communist economies.

Gaston Leval writes, “the various agrarian and industrial collectives immediately instituted economic equality in accordance with the essential principle of communism, 'From each according to his ability and to each according to his needs.' They co-ordinated their efforts through free association in whole regions, created new wealth, increased production (especially in agriculture), built more schools, and bettered public services.”[18]

While some historians portray the rural collectives as products of coercion, the truth is that rural residents voluntarily created hundreds of their own collectives in regions where there anarchist militias did not even exist. There were 900 rural collectives in the Levant, 300 in Castile, and 30 in Estremada, all regions without anarchist militias. An Anarchist FAQ summarizes, "the rural collectivisation process occurred independently of the existence of anarchist troops, with the majority of the 1,700 rural collectives created in areas without a predominance of anarchist militias."[19]

Some later anti-authoritarians have criticized the Spanish anarchists' reluctance or inability to establish the fully communist arrangements that they desired in theory. The left Communist Gilles Dauvé describes the anarchist collectives as essentially self-exploiting entities within a capitalist economy: "Equalising wages, deciding everything collectively, and replacing currency by coupons has never been enough to do away with wage labour."[20] Murray Bookchin disapprovingly describes the increasing control that certain CNT-FAI federal committees took over industry in urban parts of revolutionary Spain, supplanting workers' direct self-management.

The higher committee began to pre-empt the initiative of the lower, although their decisions still had to be ratified by the workers o f the facilities involved. The effect o f this process was to tend to centralize the economy of CNT-FAI areas in the hands of the union. The extent to which this process unfolded varied greatly fro m industry to industry and area to area, and with the limited knowledge we have at hand, generalizations are very difficult to formulate. With the entry o f the CNT -FAI into the Catalan government in 1936, the process o f centralization continued and the union-controlled facilities became wedded to the state. By early 1938, a political bureaucracy had largely supplanted the authority of the workers' committees in all “republican” -held cities. Although workers control existed in theory, it had virtually disappeared in fact.Cite error: Closing

</ref>missing for<ref>tag A spokesperson for the Valencia government's Subsecretariat of Munitions and Armament said that the war industry in Catalonia produced ten times more than the rest of the country put together.[21]Some industries, such as woodwork, syndicalized their workplaces, meaning they put the CNT in charge of managing the industry. An Anarchist FAQ writes, “In the end, the major difference between the union-run industry and a capitalist firm organisationally appeared to be that workers could vote for (and recall) the industry management at relatively regular General Assembly meetings.”[22]

Workers also syndicalized Catalonia's health care system. Founded in September 1936, the CNT-affiliated Health Workers' Union provided health care to all Catalonians. With 1,020 doctors and about 7,000 other workers, the syndicate ran 36 health centers. It had 9 autonomous zones, each of which nominated a delegate to attend weekly meetings of the Control Committee in Barcelona. The Catalan government and the municipalities paid for hospital expenses.[23]

Other industries, such as Bardalona's textile industry, confederated their workplaces. This meant that each workplace remained autonomous, while using the union to coordinate activities with other workplaces. The historian Ronald Fraser explains, “everything each mill did was reported to the union which charted progress and kept statistics. If the union felt that a particular factory was not acting in the best interests of the collectivised industry as a whole, the enterprise was informed and asked to change course.”[24]

The Levant

The Peasant Federation of Levant coordinated the economy of 900 collectives, encompassing 1,650,000 members. The federation organized the region into 54 local federations and 5 district federations. Each district instituted a rationing of supplies and a family wage. The district federations helped equalize resources between the wealthier villages and poorer villages. [25]

The town of Magdalena de Pulpis abolished money altogether. A resident explained, “Everyone works and everyone has the right to what he needs free of charge. He simply goes to the store where provisions and all other necessities are supplied. Everything is distributed free with only a notation of what he took.” Sam Dolgoff comments that the attempts to abolish money “were not generally successful,” due to the pressures of the war. Usually, towns implemented a family wage. [26]

Aragon

The Aragon Federation of Collectives coordinated the economy of 500 collectives, encompassing 433,000 members. Collectives supplied statistics on production and consumption to their District Committees, which then sent these statistics to the Regional Committee. In February of 1937, the Federation decided to abolish the exchange of national currency within and between collectives. In place of traditional money, the Regional Committee would distribute a uniform ration booklet to each collective, leaving it to each collective to decide how to distribute rations. Small proprietors were allowed to remain outside the collective as long as they didn't infringe on the collective's rights or hire wage-workers. [27]

Environment

After collectivizing the land, peasants in Aragon and the Levant applied innovative techniques to increase yields and improve the health of the soil. Peter Gelderloos writes that they used intercropping, putting shade-tolerant plants underneath orange trees.[28] Daniel Guérin describes the collectives' commitment to reforestation and diversification of crops:

Agricultural self-management was an indisputable success except where it was sabotaged by its opponents or interrupted by the war. After the Revolution the land was brought together into rational units, cultivated on a large scale and according to the general plan and directives of agronomists. The studies of agricultural technicians brought about yields 30 to 50 percent higher than before. The cultivated areas increased, human, animal, and mechanical energy was used in a more rational way, and working methods perfected. Crops were diversified, irrigation extended, reforestation initiated, and tree nurseries started.[29]

In Catalonia, the CNT shut down hazardous metal factories, which they announced were “centres for tuberculosis”.[30]

Crime

At its 1936 Saragossa conference, the CNT outlined its approach to crime, as Daniel Guérin summarzies:

With regard to crime and punishment the Saragossa conference followed the teachings of Bakunin, stating that social injustice is the main cause of crime and, consequently, once this has been removed offenses will rarely be committed. The congress affirmed that man is not naturally evil. The shortcomings of the individual, in the moral field as well as in his role as producer, were to be investigated by popular assemblies which would make every effort to find a just solution in each separate case.[31]

At a public meeting described by Gaston Leval, the Aragon town of Huesca discussed how to respond to a group of individualists that left the collective but expected the collective to take care of their elderly parents. The collective decided that they would take care of the elderly no matter what. But if the individualists did not take in their parents, then the collective would not provide these individualists with any land or solidarity. [32] Huesca's resolution demonstrates how an anarchist community can attach consequences to unsocial behavior.

In Catalonia, the anarchists cooperated with the liberals, Communists and Socialists to form a proto-statist Central Anti-Fascist Militia Committee. It took over the work of the police. Historian Bernett Bolloten writes that the power of the committee, “rested not on the shattered machinery of state but on the revolutionary militia and police squads”.[33]

Revolution

At the start of the civil war, anarchist forces defeated the fascists' July assault on Barcelona. George Orwell commented, “During the first two months of the war it was the Anarchists more than anyone else who had saved the situation, and much later than this the Anarchist militia, in spite of their indiscipline, were notoriously the best fighters among the purely Spanish forces.” [34] Orwell described Catalonia's militias as having "a nearer approach" to egalitarianism "than I had ever seen or thought I would have thought conceivable in time of war.":

Everyone from general to private drew the same pay, ate the same food, wore the same clothes, and mingled on terms of complete equality. If you wanted to slap the general commanding the division on the back and ask him for a cigarette, you could do so, and no one thought it curious. In theory at any rate each militia was a democracy and not a hierarchy. It was understood that orders had to be obeyed, but it was also understood that when you gave an order you gave it as comrade to comrade and not as superior to inferior. There were officers and N.C.O.s, but there was no military rank in the ordinary sense; no titles, no badges, no heel-clicking and saluting. They had attempted to produce within the militias a sort of temporary working model of the classless society. Of course there was not perfect equality, but there was a nearer approach to it than I had ever seen or than I would have thought conceivable in time of war. [35]

One of the anarchists' most influential military leaders was Buenaventura Durruti, who helped organize the anarchists' early defense of Barcelona and then led the 6,000-member Durruti Column. Within the column, centurias formed of at least ten people each and ten centurias formed an agrupacion. Delegates from each agrupacion met in an agrupacion committee.[36] Despite Durruti's influence as a skilled military leader, the Column largely functioned as a democracy. Emma Goldman, after visiting the Column, wrote, "No military strictness, no impositions, no disciplinary punishments existed to hold the Column together. There was nothing more than Durruti's tremendous energy, which he communicated to the others through his conduct and which made everything a whole that felt and acted in unison."[37] In one instance, a militia member asked Durutti for permission to go to Barcelona and Durruti replied, "Impossible at the moment." The milita member objected, and Durruti called a vote. The majority voted to allow the militant to leave, overruling Durruti's judgment, "and the militiaman took off for Barcelona."[38] According to Abel Paz's Durruti in the Spanish Revolution, the famous militant died on 20 November 1936 after being shot in the chest by nationalists in Madrid the previous day.[39]

The fascist side won the civil war in March of 1939. The most obvious cause of the failure of the anarchists' social revolution was the pressure and repression that it faced from the outside: from Communists as well as from the fascists. The Communists' attacks on the social revolution started with imposing bureaucratic restrictions on collectives and culminated in brutal attacks on the Barcelona anarchists in May 1937, killing 500 people. By fighting the anarchists, Stalin perhaps sought to maintain an alliance with liberal capitalist states like France and the United Kingdom. Orwell argued, “In Spain the Communist 'line' was undoubtedly influenced by the fact that France, Russia's ally, would strongly object to a revolutionary neighbour and would raise heaven and earth to prevent the liberation of Spanish Morocco.”[40]

Factors internal to the social revolution must also be considered as reasons for its ultimate failure. The CNT and FAI arguably compromised their anarchist principles by joining the capitalist governments in Catalan and in Madrid. The CNT and FAI joined the Catalan government in September 1936 and joined the Madrid government in November. Most anarchists now consider these decisions to have been unstrategic. Collaborating not only strengthened the state that would later repress the revolution, but it also inhibited the mass participation of workers and peasants that energized them and fuelled their military strength.[41] Noam Chomsky points out that Austurias, the one region where central control had not destroyed the workers' collectives, was the only area where workers continued fighting well after Franco's victory.[42] An Anarchist FAQ asserts:

The most important political lesson learned from the Spanish Revolution is that a revolution cannot compromise with existing power structures. In this, it just confirmed anarchist theory and the basic libertarian position that a social revolution will only succeed if it follows an anarchist path and does not seek to compromise in the name of fighting a "greater evil." As Kropotkin put it, a "revolution that stops half-way is sure to be soon defeated."[43]

The Anarchist FAQ contends that the anarchists may have won the war if they had refused to join the Republican government and instead called a plenary among anti-fascist forces to discuss alternatives to a Spanish state: “It is likely, given the wave of collectivization and what happened in Aragon, that the decision would have been different and the first step would have made to turn this plenum into the basis of a free federation of workers associations—i.e. the framework of a self-managed society—which could have smashed the state and ensured no other appeared to take its place.”[44]

Moroever, anarchists failed to sufficiently ally with the Moroccan independence movement, a move that Chomsky argues may have demoralized Franco's Moroccan troops and secured the success of the anarchists' social revolution.[45] Gilles Dauvé concurs, "the announcement of immediate and unconditional independence for Spanish Morrocco would, at minimum, have stirred up trouble among the shock troops of reaction."[46]

Neighboring Societies

Anarchists felt considerable pressure from the Western imperial powers, and this pressure influenced their decision to collaborate with the Catalonian and national governments. At a 23 July 1936 CNT plenary, anarchists decided not to abolish the Catalonian government, even though the region's president offered them the opportunity. Diegeo Abad de Santillan voiced one reason for allowing the government to remain; its abolition could invite British intervention.[47] When anarchists entered the government in November 1936, they naively predicted Western countries would come to aid the Spanish against Franco.

Chomsky documents how the Western powers discreetly supported Franco. For example, the British navy blockaded the Straits of Gibraltar on 11 August 1936, in response to Republican ships damaging a British consulate in Algerciras. The New York Times reported, “this action helps the [fascist] Rebels by preventing attacks on Algeciras, where troops from Morocco land.” Republican ships had been trying to capture the city to isolate the fascists from Morocco. The US also aided Franco informally; Washington urged Martin Aircraft Company in August of 1936 not to honor a pre-insurrection agreement to supply Spain with aircraft, and Washington urged Mexico not to send US war materials to Spain.[48]

Anarchist terror

Anarchists committed a significant degree of terror against actual and alleged sympathizers of fascism. As Bolloten writes, “Thousands of members of the clergy and religious orders as well as of the propertied classes were killed, but others, fearing arrest or execution, fled abroad, including many prominent liberal and moderate Republicans.”[49] The anarchist Diego Abad Santillan estimates that the Catalonian anarchists murdered between 4,000 and 5,000 rightists and members of the (overwhelmingly right-wing) Catholic clergy.[50]

Drawing on these facts, the “anarcho”-capitalist Bryan Caplan argues the “Anarchist militants' wave of murders” followed logically from their ideology of class struggle.[51] Iain McKay responds that while the anarchists' mass assassinations were inexcusable, they were carried out by a small minority of anarchists and faced fierce condemnations from the CNT-FAI. In fact, the CNT-FAI had a policy of executing anyone (even their own members) caught terrorizing innocent people. The FAI executed some anarchist militants under this policy. Moreover, McKay notes that the anarchists' murders pale in comparison to those committed by Franco's forces, who received strong support from capitalists inside and outside of Spain. In Aragon's town of Zaragoza, fascists murdered 3,000 anti-fascists, mostly CNT members. McKay comments:

“In other words, the forces supported by capitalists murdered almost as many people in one town as the armed population did in the whole of Catalonia. After Franco won the civil war, he murdered tens of thousands more (probably hundreds of thousands) and produced a nation into which capitalists happily invested. As capitalists have discovered across the world, terror is an effective means of ensuring high profits and employer power.” [52]

- ↑ Sam Dolgoff, The Anarchist Collectives: Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939, Anarchist Library, http://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/sam-dolgoff-editor-the-anarchist-collectives. 104, 40

- ↑ Noam Chomsky, “Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship” in The Chomsky Reader (New York: Pantheon Books, 1987), 102.

- ↑ Dolgoff, The Anarchist Collectives, 39.

- ↑ George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia (USA: Harcourt, Inc., 1980), 4-5.

- ↑ Martha A. Ackelsberg, Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women (OaklandL AK Press, 2005), 116

- ↑ Connor McLaughlin, “Free Women of Spain,” http://flag.blackened.net/revolt/ws/spain48.html.

- ↑ Ackelsberg, Free Women of Spain, 33.

- ↑ Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism (London: Harper Perennial, 2008).

- ↑ Daniel Guérin, Anarchism: From Theory to Practice (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1970).

- ↑ Gaston Leval, “Libertarian Democracy” in Collectives in the Spanish Revolution, Libcom.org, http://libcom.org/library/collectives-spanish-revolution-gaston-leval

- ↑ Burnett Bolloten, The Spanish Civil War: Revolution and Counterrevolution (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991). https://libcom.org/library/spanish-civil-war-revolution-counterrevolution-burnett-bolloten.

- ↑ Chomsky, “Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship”

- ↑ Bolloten, The Spanish Civil War”.

- ↑ Tom Wetzel, “Workers Power and the Spanish Revolution”. https://libcom.org/library/workers-power-and-the-spanish-revolution-tom-wetzel.

- ↑ Murray Bookchin, To Remember Spain: The Anarchist and Syndicalist Revolution of 1936, http://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/murray-bookchin-to-remember-spain-the-anarchist-and-syndicalist-revolution-of-1936.

- ↑ Bookchin, "To Remember Spain."

- ↑ An Anarchist FAQ Version 15, “I.8.4 How were the Spanish industrial collectives co-ordinated?”. http://anarchism.pageabode.com/afaq/secI8.html.

- ↑ An Anarchist FAQ, Version 15, “I.8.4 How were the Spanish industrial collectives co-ordinated?”, http://anarchism.pageabode.com/afaq/secI8.html.

- ↑ An Anarchist FAQ, Version 15, "I.8.7 Were the rural collectives created by force?", http://anarchism.pageabode.com/afaq/secI8.html#seci87.

- ↑ Gilles Dauvé, "When Insurrections Die," https://libcom.org/library/when-insurrections-die.

- ↑ Chomsky, “Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship,” 95.

- ↑ An Anarchist FAQ. Version 15, “I.8.4 How were the Spanish industrial collectives co-ordinated?”. http://anarchism.pageabode.com/afaq/secI8.html.

- ↑ Dolgoff, The Anarchist Collectives, 125-128.

- ↑ An Anarchist FAQ. Version 15, “I.8.4 How were the Spanish industrial collectives co-ordinated?”. http://anarchism.pageabode.com/afaq/secI8.html.

- ↑ Dolgoff, The Anarchist Collectives, 145-148.

- ↑ Dolgoff, The Anarchist Collectives, 100.

- ↑ Dolgoff, The Anarchist Collectives, 149-152

- ↑ Peter Gelderloos, Anarchy Works, “What about technology?”

- ↑ Guérin, Anarchism, 134-4

- ↑ Iain McKay, “Objectivity and Right-Libertarian Scholarship,” 20 January 2009, http://anarchism.pageabode.com/anarcho/caplan.html.

- ↑ Guérin, Anarchism, 123.

- ↑ Leval, “Libertarian Democracy”

- ↑ Bolloten, The Spanish Civil War.

- ↑ Orwell, Homage to Catalonia, 62.

- ↑ Orwell, Homage to Catalonia, 27.

- ↑ Trans. Chuck Morse, Abel Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution (Oakland: AK Press, 2007), 473.

- ↑ Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution, 509.

- ↑ Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution, 510.

- ↑ Paz, Durruti in the Spanish Revolution, 595-598.

- ↑ An Anarchist FAQ Version 15, “Section I.8 Does Revolutionary Spain show that libertarian socialism can work in practice?”, http://anarchism.pageabode.com/afaq/secI8.html#seci89. Chomsky, “Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship” 88-89, 102. Orwell, Homage to Catalonia, 57.

- ↑ An Anarchist FAQ Version 15, “Section I.8.11 “Was the decision to collaborate a product of anarchist theory?” http://anarchism.pageabode.com/afaq/secI8.html#seci811.

- ↑ Chomsky, “Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship.”

- ↑ An Anarchist FAQ, "I.8.13 What political lessons were learned from the revolution?", http://anarchism.pageabode.com/afaq/secI8.html#seci8.

- ↑ An Anarchist FAQ, “Section I.8”

- ↑ Chomsky, “Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship.”

- ↑ Gilles Dauvé, "When Insurrections Die," https://libcom.org/library/when-insurrections-die.

- ↑ Wetzel. Workers Power and the Spanish Revolution.

- ↑ Chomsky, Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship.

- ↑ Bolloten, The Spanish Civil War.

- ↑ Iain McKay, “Objectivity and Right-Libertarian Scholarship,” 20 January 2009, http://anarchism.pageabode.com/anarcho/caplan.html.

- ↑ Bryan Caplan, “The Anarcho-Statists of Spain: An Historical, Economic and Philosophical Analysis of Spanish Anarchism,” http://econfaculty.gmu.edu/bcaplan/spain.htm.

- ↑ McKay, “Objectivity and Right-Libertarian Scholarship”.