1999 Seattle WTO shutdown: Difference between revisions

(→N30) |

(→N30) |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Affinity groups composed of DAN members took responsibility for blocking certain “slices” of the circular area around the convention center, in order to stop WTO delegates from getting in.<ref>Steve, “Black Bloc Participant Overview” in ''The Black Bloc Papers'', ed. David van Deusen and Xavier Massot (Shawnee Mission: Breaking Glass Press, 2010), 47.</ref> The strategy was modeled on the 1972 protests against the Republican Convention in Miami, when protesters blocked delegates from attending (and a riot started).<ref>Mike Roselle, ''Tree Spiker: From Earth First to Lowbagging, Advance Uncorrected Proofs'' (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2009), 223.</ref> | Affinity groups composed of DAN members took responsibility for blocking certain “slices” of the circular area around the convention center, in order to stop WTO delegates from getting in.<ref>Steve, “Black Bloc Participant Overview” in ''The Black Bloc Papers'', ed. David van Deusen and Xavier Massot (Shawnee Mission: Breaking Glass Press, 2010), 47.</ref> The strategy was modeled on the 1972 protests against the Republican Convention in Miami, when protesters blocked delegates from attending (and a riot started).<ref>Mike Roselle, ''Tree Spiker: From Earth First to Lowbagging, Advance Uncorrected Proofs'' (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2009), 223.</ref> | ||

Early in the morning on 30 November, DAN affinity groups swarmed the streets, successfully blocking WTO delegates’ entrance. A delegate asked a police officer, “How do we get inside?” The cop responded, “Well, sir...right now there ''is'' | Early in the morning on 30 November, DAN affinity groups swarmed the streets, successfully blocking WTO delegates’ entrance. A delegate asked a police officer, “How do we get inside?” The cop responded, “Well, sir...right now there ''is'' no way to get inside.” Opening ceremonies were canceled.<ref> Crimethinc, ''N30'', 9, 33-34.</ref> | ||

Police responded very brutally with tear gas and rubber bullets.<ref>''The Black Bloc Papers'', 41.</ref> The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Washington State later condemned the police violence: “Police repeatedly used force -- especially chemical weapons -- in ways that were more aggressive and heavy-handed than the situation warranted.”<ref>ACLU of Washington, “ACLU Report Says Response To Seattle WTO Protests was 'Flawed, Out of Control',” 5 July 2000, https://www.aclu.org/news/aclu-report-says-response-seattle-wto-protests-was-flawed-out-control.</ref> | Police responded very brutally with tear gas and rubber bullets.<ref>''The Black Bloc Papers'', 41.</ref> The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Washington State later condemned the police violence: “Police repeatedly used force -- especially chemical weapons -- in ways that were more aggressive and heavy-handed than the situation warranted.”<ref>ACLU of Washington, “ACLU Report Says Response To Seattle WTO Protests was 'Flawed, Out of Control',” 5 July 2000, https://www.aclu.org/news/aclu-report-says-response-seattle-wto-protests-was-flawed-out-control.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 18:07, 13 September 2023

On 30 November 1999, 75,000 people demonstrated in Seattle and successfully shut down a summit of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Anarchists organized most of the direct action components and engaged in many activities including street blockades, serving food, and breaking the windows of corporate property. They succeeded in “preventing the opening ceremonies from, well, opening.” Around the world, people protested as part of a global day of action. Days into the summit, African and Caribbean delegates walked out and shut down the conference entirely. Over six hundred protesters were arrested in Seattle.[1] Bringing critiques of neoliberal “free trade” and corporate power to the forefront of people’s attention worldwide, the demonstrations played an enormous role in attracting new participants and supporters to the alter-globalization movement.

The demonstrations involved a diverse range of tactics including the delegates’ walkout and activists’ permitted marches, nonviolent civil disobedience, and property destruction. To this day, people argue about which tactics were more effective than others, but the combination did capture global headlines, delay the summit’s opening, and prevent the WTO from reaching agreement. According to the Global Nonviolent Action Database, the campaign “was extremely successful.”[2]

Planning

The direct actions emerged out of calls to action issued by Peoples’ Global Action (PGA), a network that had grown out of the Zapatistas’ international encuentros “for humanity and against neoliberalism.” At a nonviolent direct action training organized by the Ruckus Society (a nonprofit organization with links to the direct action movement), people formed the Direct Action Network (DAN) in order to coordinate the Seattle protests. DAN organized horizontally using consensus decision-making.[3] San Francisco Art and Revolution, the Earth First! Journal, and many other groups helped publicize the impending WTO shutdown.[4]

The protests targeted the WTO, a global trade body dominated by the Global North and biased against poorer nations. Trade talks tended to pressure nations to weaken labor and environmental negotiations in the interests of “free trade.” The overall narrative of the protests was captured by Rainforest Action Network’s banner drop from a Seattle crane a week before the shutdown. The banner showed two arrows pointing in opposite directions. One arrow said “Democracy.” The other said “WTO.” [5]

Prior to the WTO summit’s 30 November opening (a date activists called N30), many direct action participants stayed at 420 Denny Space, where Anarchists ran trainings and skill shares, fed participants, and mass-produced lock-boxes (tar-covered PVC pipes, through which protesters link arms so it’s difficult for police to move them).[6] Actually, Earth First!’s direct action manual says this was the first time activists built lock-boxes out of PVC pipes instead of heavier metal pipes.[7]

N30

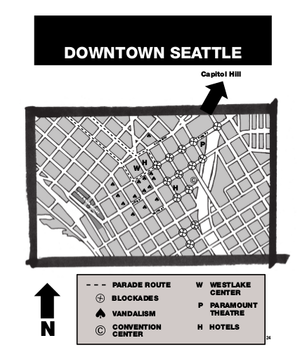

Affinity groups composed of DAN members took responsibility for blocking certain “slices” of the circular area around the convention center, in order to stop WTO delegates from getting in.[8] The strategy was modeled on the 1972 protests against the Republican Convention in Miami, when protesters blocked delegates from attending (and a riot started).[9]

Early in the morning on 30 November, DAN affinity groups swarmed the streets, successfully blocking WTO delegates’ entrance. A delegate asked a police officer, “How do we get inside?” The cop responded, “Well, sir...right now there is no way to get inside.” Opening ceremonies were canceled.[10]

Police responded very brutally with tear gas and rubber bullets.[11] The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Washington State later condemned the police violence: “Police repeatedly used force -- especially chemical weapons -- in ways that were more aggressive and heavy-handed than the situation warranted.”[12]

Labor

Meanwhile, the AFL-CIO, a labor union with a conservative, pro-business leadership, lead a permitted, non-disruptive march far from the direct actions. In Crimethinc’s analysis, “the AFL-CIO’s strategic target was supporting and legitimating President Clinton’s actions at the conference through purely symbolic displays by a loyal opposition.”[13] Their messaging stayed clear of criticizing the administration of the pro-WTO president.[14]

Many rank-and-file unionists, however, broke away from that march and joined DAN’s more disruptive demonstrations.[15] Some unionists overcame the mainstream labor movement’s traditional antagonism toward environmentalism. They marched alongside with environmentalists dressed as sea turtles and holding signs “Teamsters and Turtles, Together at Last.”[16]

Members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and Earth First! organized rank-and-file members of the longshore workers and steelworkers to join the direct actions:

Both the IWW and Earth First! were part of the anti-capitalist faction which sought to block the negotiations from proceeding. As early as late Spring of 1999, at an anarcho-syndicalist “summit” we had organized called I-99, the Bay Area IWW took part in planning actions as part of the anti-WTO protests. These consisted of several efforts: (1) organizing a large contingent of IWW members and like minded class struggle unionists to protest in Seattle; (2) Organizing rank and file members of the ILWU to push for a vote to shut down the west coast ports during the WTO negotiations; (3) bringing large numbers of the United Steelworkers who were still engaged in a struggle with Kaiser Aluminum (owned by Maxxam corporation) and were working alongside Earth First! against their common adversary, Charles Hurwitz; (4) supporting various Seattle public workers unions, including the bus drivers, whose contracts were up at the time and whose bosses were pushing for concessions.[17]

Black Bloc

About 100 to 200 people, mostly Anarchists, formed a black bloc, meaning they dressed in black and wore bandannas or masks to disguise their identities from police and bosses.[18] Many of them had come from backgrounds in Earth First! and the radical ecological movement.[19] On the evening of 29 November and the afternoon of 30 November, the black bloc attacked the private property of multinational corporations.

Communications scholars have since found that the black bloc “catapulted the protests into national headlines” and thus “drew more [media] attention to the issues.”[20]

The ACME Collective, an Anarchist section of the black bloc explained that the bloc attacked:

Fidelity Investment (major investor in Occidental Petroleum, the bane of the U’wa tribe in Colombia), Bank of America, US Bancorp, Key Bank and Washington Mutual Bank (financial institutions key in the expansion of corporate repression) Old Navy, Banana Republic and the GAP (as Fisher family businesses, rapers of Northwest forest lands and sweatshop laborers) NikeTown and Levi’s (whose overpriced products are made in sweatshops) McDonald’s (slave-wage fast-food peddlers responsible for destruction of tropical rainforests for grazing land and slaughter of animals) Starbucks (peddlers of an addictive substance whose products are harvested at below-poverty wages by farmers who are forced to destroy their own forests in the process) Warner Bros. (media monopolists) Planet Hollywood (for being Planet Hollywood).[21]

Jeffrey St. Clair reported from the ground that the black bloc were very mindful and targeted in their actions:

The manager of Starbucks whined about how “mindless vandals” destroyed his window and tossed bags of French Roast onto the street. But the vandals weren’t mindless. They didn’t bother the independent streetside coffee shop across the way. Instead, they lined up and bought cup after cup. No good riot in Seattle could proceed without a cup of espresso.[22]

In response to police violence, some black bloc participants threw bottles and rocks and dragged dumpsters to the streets and lit them on fire.[23] In addition, about 100 local teenagers started looting and graffiting.[24] Anarchists were generally thrilled by these teenagers’ participation. For example, a person in the documentary Breaking the Spell says:

There was this big, big push before the WTO happened to get people from diverse backgrounds and something other than the activist, middle-class thing that was going on. It happened very spontaneously. People with the reason to be fucking shit up, people who have the most reason to be breaking the windows of Nike, were doing it. And that was one of the best aspects of it. People who needed shoes were breaking the windows and getting shoes. And that’s the way it should be.[25]

Peace Police

Some pacifists—derided as “peace police”—attacked black bloc participants and tried to get them arrested. ACME Collective reports, “On at least 6 separate occasions, the so-called ‘nonviolent’ activists physically attacked individuals who targeted corporate property. Some even went so far as to stand in front of the Niketown super store and shove the Black Bloc away.”[26]

Lori Wallach of Public Citizen claims that on 29 November, unionists “picked up” Anarchists and carried them to the police:

Our people actually picked up the anarchists. Because we had with us steelworkers and longshoremen who, by sheer bulk, were three or four times larger. So we had them literally just sort of, a teamster on either side, just pick up an anarchist. We’d walk him over to the cops and say this boy just broke a window. He doesn’t belong to us. We hate the WTO, so does he, maybe, but we don’t break things. Please arrest him.[27]

Medea Benjamin was quoted in the New York Times as having asked on 30 November, “Where are the police? These anarchists should have been arrested.”[28]

Where was the color?

Elizabeth Betita Martinez criticizes how N30 organizers did not, by and large, make a concerted effort to inform people of color about the WTO or bring them to Seattle. People of color only comprised an estimated 5 percent of the demonstrators.

Among community activists of color, the Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN) delegation led by Tom Goldtooth conducted an impressive program of events with Native peoples from all over the U.S. and the world. A 15-member multi-state delegation represented the Southwest Network for Environmental and Economic Justice based in Albuquerque, which embraces 84 organizations primarily of color in the U.S. and Mexico; their activities in Seattle were binational. Many activist youth groups of color came from California, especially the Bay Area, where they have been working on such issues as Free Mumia, affirmative action, ethnic studies, and rightwing laws like the current Proposition 21 "youth crime" initiative. Seattle-based forces of color that participated actively included the Filipino Community Center and the international People’s Assembly, which led a march on Tuesday despite being the only one denied a permit

Betita Martinez summarizes:

Yet if only a small number of people of color went to Seattle, all those with whom I spoke found the experience extraordinary. They spoke of being changed forever. "I saw the future." "I saw the possibility of people working together." They called the giant mobilization "a shot in the arm," if you had been feeling stagnant.[29]

Global Action

In the days leading up to N30, people took direct action around the world. Three thousand rallied in Seoul, South Korea. 75,000 protested in eighty cities across France. Students in Milan, Italy occupied a university’s biology facilities in protest of the WTO’s imposition of biotechnology. People performed street theater in Santos, Brazil. Food Not Bombs distributed food and leaflets in Prague, Czech Republic. In Haifax, England, Earth First!ers occupied a Nestle factory. In Manchester, England, fifty people occupied a bank branch and blockaded a road. In Lille, France, twelve banks were painted red. In Narmada Valley, India, more than 1,000 demonstrated. In Nashville, activists occupied Vice President and Democratic Party presidential candidate Al Gore’s campaign offices with a giant Ronald McDonald puppet. Groups occupied a road in Buenos Aires, Argentina. More than 8,000 marched in Pakistan with a “Shut down the WTO” banner.[30]

- ↑ notes from nowhere, We are Everywhere (New York: Verso, 2003), 204, 207.

- ↑ Summer Miller-Walfish, “Activists prevent World Trade Organization conference in Seattle, 1999,” Global Nonviolent Action Database, 12 May 2010, https://nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu/content/activists-prevent-world-trade-organization-conference-seattle-1999.

- ↑ David Graeber, Direct Action: An Ethnography (Oakland: AK Press, 2009), iv, xiii, 290.

- ↑ Do or Die, “Countdown to the Battle of Seattle,” http://www.eco-action.org/dod/no9/seattle_chronology.html.

- ↑ Sparki, “The Rainforest Action Complex,” 28 September 2009, https://www.ran.org/the_rainforest_action_complex.

- ↑ Crimethinc, N30 The Seattle WTO Protests: A memoir and analysis, with an eye to the future, 2006, https://crimethinc.com/zines/n30-the-seattle-wto-protests, 4.

- ↑ Earth First!, Direct Action Manual, Third Edition, 117.

- ↑ Steve, “Black Bloc Participant Overview” in The Black Bloc Papers, ed. David van Deusen and Xavier Massot (Shawnee Mission: Breaking Glass Press, 2010), 47.

- ↑ Mike Roselle, Tree Spiker: From Earth First to Lowbagging, Advance Uncorrected Proofs (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2009), 223.

- ↑ Crimethinc, N30, 9, 33-34.

- ↑ The Black Bloc Papers, 41.

- ↑ ACLU of Washington, “ACLU Report Says Response To Seattle WTO Protests was 'Flawed, Out of Control',” 5 July 2000, https://www.aclu.org/news/aclu-report-says-response-seattle-wto-protests-was-flawed-out-control.

- ↑ Crimethinc, N30, 19.

- ↑ Jeffrey St. Clair, “Seattle Diary,” Counterpunch, 16 December 1999, https://www.counterpunch.org/1999/12/16/seattle-diary/.

- ↑ Crimethinc, N30, 17.

- ↑ St. Clair, “Seattle Diary.”

- ↑ Steve Ongerth, “Capital Blight: To Wrench or Not to Wrench, a Response,” Earth First! Newswire, 2 November 2013, https://earthfirstjournal.org/newswire/2013/11/02/capital-blight-to-wrench-or-not-to-wrench-a-response/.

- ↑ Crimethinc, N30, 21.

- ↑ Earth First!

- ↑ Kevin Michael DeLuca and Jennifer Peeples, “From public sphere to public screen: democracy, activism, and the ‘violence’ of Seattle,” Critical Studies in Media Communication 19, no. 2: 125-151, DOI: 10.1080/07393180216559.

- ↑ ACME Collective, “N30 Black Bloc Communique” in The Black Bloc Papers, ed. David van Deusen and Xavier Massot (Shawnee Mission: Breaking Glass Press, 2010), 42.

- ↑ St. Clair, “Seattle Diary.”

- ↑ The Black Bloc Papers, 41.

- ↑ Crimethinc, N30, 42.

- ↑ Breaking the Spell, 1999 or 2000, 63:00, https://sub.media/video/breaking-the-spell/.

- ↑ ACME Collective, “N30 Black Bloc Communique,” 42.

- ↑ Francis Dupuis-Déri, Who’s Afraid of the Black Blocs? Anarchy in Action Around the World, trans. Lazer Ledehndler (Oakland: PM Press, 2014).

- ↑ Dupuis Déri, 'Who’s Afraid of the Black Blocs?

- ↑ Elizabeth Betita Martinez, "Where Was the Color in Seattle?Looking for reasons why the Great Battle was so white," Colorlines, 10 March 2000, https://www.colorlines.com/articles/where-was-color-seattlelooking-reasons-why-great-battle-was-so-white.

- ↑ Do or Die, “Countdown.”