French Revolution and Anarchy

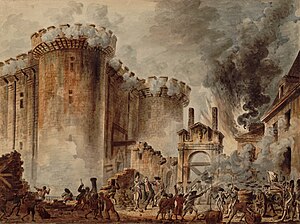

Participatory forces, notably the Parisian sections and the enragés, played an important role in the French Revolution (1789) that overthrew the French monarch and reshaped world politics. According to Immanuel Wallerstein, the French Revolution made the desirability of social change and popular sovereignty a part of global common sense.[1]

The enragés (rabids), popular intellectuals of the small-propertied class called the sans-culottes ("without culottes" - culottes were knee-breaches worn by aristocrats), argued that the French Revolution was actually comprised of three revolutions. The first revolution began in 1789 and describes the overthrow of the king and abolition of feudalism. The second revolution began in 1792 and describes the establishment of the National Convention, a supposedly radical legislature designed to supersede the moderate Legislative Assembly. The third revolution, called for by the enragés themselves in 1793, unsuccessfully attempted to replace the National Convention with a direct democratic form of governance.[2] Women among the sans-culottes formed the Club of Revolutionary Republican Women Citizens. Leaders included Claire Lacombe and Pauline Léon.[3]

The limits of the French Revolution can be seen in its relation to the Haitian Revolution. Although, by 1792, Parisian masses did support Haitian independence[4], the norm was not always for revolutionaries to support liberation of the French colony and its slaves.[5]

Parisian sections

In preparation of the 1789 Estates General meeting, the king set up sectional assemblies, local gatherings across France that chose delegates to select representatives for the Third Estate. Long after they had served their initial purposes, many assemblies continued meeting.

The sectional assemblies began governing local affairs in Paris and other large cities. Paris's 48 sections extended participation to all male adults, and in some cases to women. By 1972-3, the Parisian sections assumed responsibility for policing, finance, defense and supplies. Each section sent six delegates to the confederal Commune governing Paris.[6] Peter Kropotkin writes, “the Commune of Paris was not to be a governed State, but a people governing itself directly — when possible — without intermediaries, without masters”.[7]

Each section organized through committees which Bookchin groups into three categories. Civil committees handled food supply, finance, and record-keeping. Vigilance committees handled security. And ad hoc committees addressed needs such as finding work for the unemployed, collecting gunpowder, planning outdoor suppers, and mobilizing recruits for the war.[8]

Third Revolution

The enragés were popular speakers and writers who articulated ideas of the sans-culottes. Jean Francois Varlet, one of the enragés, advocated direct democracy across France, in which sectional assemblies would send recallable delegates to coordinate national affairs.[9]

On March 10 1793, Varlet and other enragés staged a failed insurrection against the Convention. A few days later, Varlet spoke before the middle-class Jacobin Club and called for a larger insurrection, a “third revolution” for direct sectional democracy and against the moderate Girondins who controlled the Convention. Following this call to arms, delegates of the sections met at Eveche on 2 April 1793, and on 28 May, they appointed Committee of Six to plan the uprising. On the night of May 30, the Eveche assembly announced Paris was in a state of insurrection against the Girondins.[10]

Together, the Jacobins and enragés succeeded in forcing the Girondins from power. 80,000 armed people surrounded the Convention and took over.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag The Jacobins' leader Maximilien de Robespierre insisted on replacing Christianity with a new state religion called the Cult of the Supreme Being. They disbanded opposing groups including, on 30 October 1793, the Club of Revolutionary Republican Women.[11]

During this reign of terror, with Robespierre as head of state, the Jacobins formally executed some 16,594 people by the guillotine. This does not include those of their victims who died in prison or were beaten in the streets. The vast majority of those guillotined were from the lower-classes. Only 14 percent were from the clergy or aristocracy, the rest from the "Third Estate" that the revolution was supposed to defend. Robespierre justified the repression, saying "The revolutionary government has nothing in common with anarchy. On the contrary, its goal is to suppress it in order to ensure and solidify the reign of law."[12]

Varlet denounced the Jacobins' rule as "a disgusting dictatorship" and denounced the Jacobins' concept of revolutionary government:

"What a social monstrosity, what a masterpiece of Machiavellianism is this revolutionary government! To any rational being, government and revolution are incompatible, unless the people wishes to set its constituted authorities in perpetual insurrection against itself, which would be absurd."[13]

Thermidor

The Jacobins implemented their own calendar with months like "Thermidor," and on the 9th of Thermidor, which was 27 July 1794, counter-revolutionaries succeeded in ousting the Jacobins. Robespierre was executed by the guillotine.[14]

Some accounts say the "revolution was over after Thermidor 1794,"[15], whereas others suggest that "there was a continuity in the Revolution beyond 9 Thermidor."[16] In any case, the revolution never recovered, and the revolution was indisputably over after Napoleon Bonaparte took over France as dictator in 1799.

- ↑ Immanuel Wallerstein, World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2004), 51.

- ↑ Murray Bookchin, The Third Revolution: Popular Movements in the Revolutionary Era, Volume 1.

- ↑ Eric Hazan, A People's History of the French Revolution (London: Verso, 2017), 250.

- ↑ [Anarchy in the Haitian Revolution]

- ↑ Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, "Decolonization is Not a Metaphor," Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1-40.

- ↑ Janet Biehl, The Politics of Social Ecology: Libertarian Municipalism.

- ↑ Peter Kropotkin, The Great French Revolution 1789-1793, http://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/petr-kropotkin-the-great-french-revolution-1789-1793.

- ↑ Bookchin, The Third Revolution, 319-320.

- ↑ Murray Bookchin, The Third Revolution: Volume I (Bloomsbury Academic, 1996), 325.

- ↑ Kropotkin, ibid.

- ↑ Hazan, A People's History, 253, 371.

- ↑ Crimethinc, "Against the Logic of the Guillotine," 8 April 2019, https://crimethinc.com/2019/04/08/against-the-logic-of-the-guillotine-why-the-paris-commune-burned-the-guillotine-and-we-should-too.

- ↑ Jean Varlet, "The Explosion," in Anarchism: A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas: Volume One, from Anarchy to Anarchism (300 CE to 1939) edited by Robert Graham (Montreal: Black Rose Books, 2005), 24.

- ↑ Crimethinc, "Against the Logic."

- ↑ Harman, A People's History, 300.

- ↑ Hazan, A People's History, 413.