Neolithic Mesopotamia

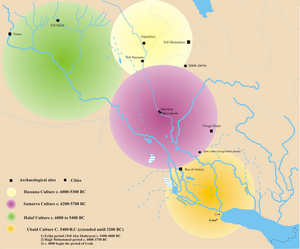

From Greek words for middle (meso) and river (potamos), Mesopotamia describes the northern Fertile Crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what's now Iraq. The Hassuna, Samarra, and Halaf cultures displayed decentralized and egalitarian characteristics which would continue into even into the Bronze Age's first stages including in early Uruk.

Jarmo

Jarmo was an agricultural village from 7090 to 4950 BCE. It was home to around 150[1] to 300 people. Jarmo had no defensive walls and no weapons beyond arrowheads for small-animal hunting. People lived in 20 by 20 foot mud houses, each with three rooms, a courtyard and two fences. One dwelling was larger than the others, perhaps a communal building although archeologist Robert Braidwood thought a priest or chief lived there. Religious items were predominantly pregnant female figurines. With digging sticks and flint sickles, farmers grew barley, wheat, and legumes and had domesticated sheep and goats. "To judge from the scarcity of wild animals’ remains, the Jarmoites did very little hunting," Time reported in 1951.[2]

Based on interviews with archeologists, the New York Times in 1986 described Jarmo as a "village whose inhabitants lived a simple life based on subsistence agriculture. Each family was more or less independent, had its own house, raised its own livestock and made its own tools. There was no craft specialization, no evidence of organized trade or of a social hierarchy." Its relative egalitarianism was reminiscent of the earlier Neolithic as opposed to the "complex, sophisticated economic and social systems developed 7,000 to 9,000 years ago."[3]

Hassuna, Halaf and Samarra

The Hassuna, Halaf, and Samarra cultures from 6000 to 5000 BCE showed no class stratification. The former two relied on rain-fed agriculture, while the Samarra culture introduced irrigation.

Hassuna culture began around 6000 BCE. People lived in small villages, each with similarly sized and styled houses and with a communal granary. Female figurines were common. “Nothing has been found that indicates special buildings as the seat of a chief,” writes Heide Goettner-Abendroth.[4]

Halaf culture was characterized by 1-2 hectare villages, with surrounding 8-hectare nodes, forming a widespread “egalitarian” and “distributed network” with a “lack of domination” according to archeologit Charles Maisels. Each dwelling had a dome called a ‘’tholos’’ and some had rectangular antechambers.[5] Marcella Frangipane, another archeologist, finds an “absence of any differences of rank or social status” when looking at the quantity and quality of burial goods. Moreover, communal storage buildings stocked with counting tokens suggest to Frangipane a system of “egalitarian distribution.” [6]

Widespread distribution of stamp seals and counting tokens, “not just accessible for a few prominent individuals but for everyone in the communities” suggest to Goettner-Abendroth “an extensive network of interchange relations’ based “not through coercion, but rather through vast inclusive commonness based on reciprocity.” Furthermore, she observes “no evidence” of “a social hierarchy in Halaf.” Figurines of females and children, without adult males, perhaps represented matrilinearity.[7]

Succeeding the Hassuna culture, the Samarra culture were “the first to invent an artificial irrigation of gardens and fields.” Goettner-Abendroth argues they organized this irrigation “by means of community agreement without any leader responsible for the planning. Stamp seals and counting tokens helped to allocate these fairly to each household; they are clan marks rather than signs of private ownership.”[8] Samarra culture lasted until around 5000 BCE.[9]

However, Frangipane hypothesizes a family-based rather than community-based economy with a relative absence of administrative redistribution at Samarra sites compared to the Halaf culture. One Samarra site had “no collective buildings” and another had only a granary which “does not seem large enough to be interpreted as a communal storehouse for the entire community.” And there were “no signs” of “products pooled in common and then redistributed.”[10]

Ubaid culture

Migrants from the Samarra region established the Ubaid culture in fifth-century BCE South Mesopotamia and brought with them irrigation techniques and female figurines. They were the “predecessor of the later Sumer culture” and would end up “merging peacefully with the Halaf culture of North Mesopotamia.[11]

Maisels describes the Ubaid culture as a series of patriarchal households within an otherwise non-hierarchical culture in which there was “just no role for a ‘chief’,”[12] Frangipane calls it a “vertical egalitarian system,” in which “substantial equality and economic self-reliance were accompanied by a system of social and kinship relations which gave and legitimized a kind of privileged status to certain members of the community depending upon their genealogical position, true or presumed, entitling them to represent the community and take up its governance.”[13] Graeber and Wengrow observe “a certain self-conscious form of standardization, a social egalitarianism” within the culture:

In fact this entire period, lasting around 1,000 years (archaeologists call it the ‘Ubaid, after the site of Tell al-‘Ubaid in southern Iraq), was one of innovation in metallurgy, horticulture, textiles, diet and long-distance trade; but from a social vantage point, everything seems to have been done to prevent such innovations becoming markers of rank or individual distinction – in other words, to prevent the emergence of obvious differences in status, both within and between villages. Intriguingly, it is possible that we are witnessing the birth of an overt ideology of equality in the centuries prior to the emergence of the world’s first cities, and that administrative tools were first designed not as a means of extracting and accumulating wealth but precisely to prevent such things from happening.[14]

Less charitably, Abdullah Öcalan calls Ubaid “the first observed initial patriarchal culture prior to state formation” and describes “the combination rule of the shaman (a type of priest), the sheikh (experienced ruler of the society), and military chief (who has the physical power) first took root.”[15]

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jarmo

- ↑ Science: The Earliest Farmers, Time, 22 October 1951, https://time.com/archive/6617936/science-the-earliest-farmers/.

- ↑ William K. Stevens, "PREHISTORIC SOCIETY: A NEW PICTURE EMERGES," New York Times, 16 December 1986.

- ↑ Heide Goettner-Abendroth, ‘’Matriarchal Societies of the Past and the Rise of Patriarchy: West Asia and Europe’’, trans. Hope Hague, Simone Plaza and Tracy Byrne (New York: Peter Lang, 2023), 310.

- ↑ Charles Maisels, ‘’Early Civilizations of the Old World: The Formative Histories of Egypt, The Levant, Mesopotamia, India and China’’ (London: Routledge, 1999), 137-143.

- ↑ Marcella Frangipane, “Different types of egalitarian societies and the development of inequality in early Mesopotamia,” ‘’World Archaeology’’ 39 (no. 2): 151-176.

- ↑ Goettner-Abendroth, ‘’Matriarchal Societies of the Past’’, 312.

- ↑ Goettner-Abendroth, ‘’Matriarchal Societies of the Past’’, 313-4.

- ↑ Maisels, ‘’Early Civilization’’, 125.

- ↑ Frangipane, “Different Types.”

- ↑ Goettner-Abendroth, ‘’Matriarchal Societies of the Past’’, 314-6.

- ↑ Maisels, 156-7.

- ↑ Frangipane, “Different types.”

- ↑ David Graeber and David Wengrow, ‘’The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity’’ (New York: Farar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), 422-3, 462.

- ↑ Abdullah Öcalan, ‘’Capitalism: The Age of Unmasked Gods and Naked Kings: Manifesto for a Democratic Civilization, Volume II’’, trans. Havin Guneser (Porsgrunn: New Compass Press, 2017), 66, 134. Retrieved from https://files.libcom.org/files/ManifestoforaDemocraticCivilizationvol2.pdf.