Nishnaabeg: Difference between revisions

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

In Nishnaabeg tradition, children's education is self-directed, and children are encouraged to learn what the land and animals teach them. For example, a legend tells of a girl named Kwezen who watched a red squirrel nibbling on a tree. Kwezens decided to drill a hole and drink the sap herself. She showed the sap to her mother, who showed it to the broader community. Ever since, the community has collected sap. According to Leanne Simpson, Kwezens "already understands the importance of observation and learning from our animal teachers."<ref>Leanne Simpson, "Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation," ''Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society'' 33, no. 3 (2014), 2-6. https://decolonization.org/index.php/des/article/view/22170.</ref> In this culture, individuals "carry the responsibility for generating meaning within their own lives."<ref>Simpson, "Land as pedagogy," 11.</ref> | In Nishnaabeg tradition, children's education is self-directed, and children are encouraged to learn what the land and animals teach them. For example, a legend tells of a girl named Kwezen who watched a red squirrel nibbling on a tree. Kwezens decided to drill a hole and drink the sap herself. She showed the sap to her mother, who showed it to the broader community. Ever since, the community has collected sap. According to Leanne Simpson, Kwezens "already understands the importance of observation and learning from our animal teachers."<ref>Leanne Simpson, "Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation," ''Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society'' 33, no. 3 (2014), 2-6. https://decolonization.org/index.php/des/article/view/22170.</ref> In this culture, individuals "carry the responsibility for generating meaning within their own lives."<ref>Simpson, "Land as pedagogy," 11.</ref> | ||

Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg culture considers children to be "full citizens with the same rights and responsibilities as adults," according to Leanne Simpson.<ref>Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, ''As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance'' (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 3.</ref> | Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg culture considers children to be "full citizens with the same rights and responsibilities as adults," according to Leanne Betasamosake Simpson.<ref>Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, ''As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance'' (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 3.</ref> | ||

Nishnaabeg traditions did not have a strict gender binary.<ref>Simpson, ''As We Have Always Done'', 128.</ref> The Ojibwe had words for people who were assigned one gender at birth but adopted the traits of the other gender. Someone who was assigned maleness but chose to be a woman was called ''ikwekaazo'' (one who endeavors to be like a woman), and someone who was assigned femaleness but cohse to be a man was called ''ininiikaazo'' (one who endeavors to be like a man). According to Nishnaabeg historian Anton Treuer, "Both were considered to be strong spiritually, and they were always honored, especially during ceremonies."<ref>Simpson, ''As We Have Always Done'', 131.</ref> | |||

Potawatomi culture encourages sharing and portrays a monster named Windigo who "suffers from the illness of taking too much and sharing too little."<ref>Robin Wall Kimmerer, "The Serviceberry: An Economy of Abundance," ''Emergence Magazine'', 2020, https://emergencemagazine.org/story/the-serviceberry/.</ref> | Potawatomi culture encourages sharing and portrays a monster named Windigo who "suffers from the illness of taking too much and sharing too little."<ref>Robin Wall Kimmerer, "The Serviceberry: An Economy of Abundance," ''Emergence Magazine'', 2020, https://emergencemagazine.org/story/the-serviceberry/.</ref> | ||

70% of the Potawatomi language consists of verbs, comprising what Robin Wall Kimmerer calls a "grammar of animacy." Rather than speaking of other beings or features as an "it," one typically speaks in terms of processes. | 70% of the Potawatomi language consists of verbs, comprising what Robin Wall Kimmerer calls a "grammar of animacy." Rather than speaking of other beings or features as an "it," one typically speaks in terms of processes. For example, a bay is expressed with a verb meaning "to be a bay" (''wiikwegamaa'').<ref>Robin Wall Kimmerer, ''Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of Plants'' (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013), 54-55.</ref> | ||

=Decisions= | =Decisions= | ||

" | From the village to tribal levels, the Potawatomi historically made decisions by consensus at public assemblies. | ||

Leanne Betasamoksake Simpson writes, "Authoritarian power—aggressive power that comes from coercion and hierarchy—wasn’t a part of the fabric of Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg philosophy or governance, and so it wasn't a part of our families."<ref>Simpson, ''As We Have Always Done'', 4.</ref> Simspon elaborates, "Stable governing structures emerged when necessary and dissolved when no longer needed. Leaders were also recognized (not self-appointed) and then disengaged when no longer needed."<ref>Simson, ''As We Have Always Done'', 3.</ref> | |||

Further analysis is given by ''Sprout Distro'': | |||

<blockquote> | |||

In The People of the Three Fires: The Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan author James A. Clifton explains how Potawatomi society was structured with regard to its decision-making. What he outlines is a structure that bears many similarities to what anarchists desire: a society based on networked groups (in this case villages) that make decisions using consensus. Clifton writes: | |||

<blockquote> | |||

“…public councils and consensus-seeking public debate were regularly conducted locally, on a smaller scale, about matters affecting the local community, not the tribe as a whole. Important decisions affecting kin groups and villages, just like those involving the whole tribe, had to be thrashed out in public forums open to all. Since such decisions were arrived at by consensus rather than by majority vote, there was little room left for dispute or frustration among a minority on any issue. The emphasis on public debate, on consensus, and on the sharing and decentralization of political power reflects the great value the Potawatomi placed on equality in both the political decision-making process and the distribution of economic resources.” | |||

</blockquote> | |||

Clifton also discusses a council of all Potawatomi villages that took place in 1668 and uses it to explain how decisions were made. The Wkamek (leaders/representatives) gathered together to discuss the issue (in this a trade dispute with the French). Sitting immediately behind each individual Wkama were the kinsfolk they represented who were there to check in on the Wkamek behavior to assure that their actions and statements reflected the villages’ desires. The decision that was reached was the product of consensus and was accepted by everyone. | |||

When solving internal disputes, the Potawatomi’s practice was similar to what many anarchists talk about when they speak of voluntary association. Rather than require unanimity and conformity, the Potawatomi understood that factions occasionally did form. The solution wasn’t to chastise members who held different opinions; rather they were encouraged to split off from the community and settle elsewhere and establish their own villages.<ref>https://www.sproutdistro.com/2011/10/07/indigenous-forms-of-consensus/.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

=Economy= | =Economy= | ||

Latest revision as of 15:18, 6 July 2023

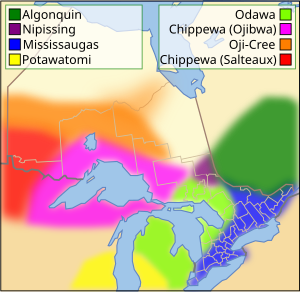

The Nishnaabeg (or Anishaabeg), meaning "the people," refers to an indigenous nation encompassing the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Mississauga, Saulteaux, and Omàmìwinini. At different points in history, the peoples of this nation have formed confederacies.[1] They reside in the lands today colonized by the "United States" and "Canada."

Culture

Nishnaabeg tradition centers around a set of ethics, values and practices called Bimaadiziwin, "living the good life." The culture balances "strong individual autonomy and freedom" with the "needs of the collective" and with "the natural world."[2]

In Nishnaabeg tradition, children's education is self-directed, and children are encouraged to learn what the land and animals teach them. For example, a legend tells of a girl named Kwezen who watched a red squirrel nibbling on a tree. Kwezens decided to drill a hole and drink the sap herself. She showed the sap to her mother, who showed it to the broader community. Ever since, the community has collected sap. According to Leanne Simpson, Kwezens "already understands the importance of observation and learning from our animal teachers."[3] In this culture, individuals "carry the responsibility for generating meaning within their own lives."[4]

Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg culture considers children to be "full citizens with the same rights and responsibilities as adults," according to Leanne Betasamosake Simpson.[5]

Nishnaabeg traditions did not have a strict gender binary.[6] The Ojibwe had words for people who were assigned one gender at birth but adopted the traits of the other gender. Someone who was assigned maleness but chose to be a woman was called ikwekaazo (one who endeavors to be like a woman), and someone who was assigned femaleness but cohse to be a man was called ininiikaazo (one who endeavors to be like a man). According to Nishnaabeg historian Anton Treuer, "Both were considered to be strong spiritually, and they were always honored, especially during ceremonies."[7]

Potawatomi culture encourages sharing and portrays a monster named Windigo who "suffers from the illness of taking too much and sharing too little."[8]

70% of the Potawatomi language consists of verbs, comprising what Robin Wall Kimmerer calls a "grammar of animacy." Rather than speaking of other beings or features as an "it," one typically speaks in terms of processes. For example, a bay is expressed with a verb meaning "to be a bay" (wiikwegamaa).[9]

Decisions

From the village to tribal levels, the Potawatomi historically made decisions by consensus at public assemblies.

Leanne Betasamoksake Simpson writes, "Authoritarian power—aggressive power that comes from coercion and hierarchy—wasn’t a part of the fabric of Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg philosophy or governance, and so it wasn't a part of our families."[10] Simspon elaborates, "Stable governing structures emerged when necessary and dissolved when no longer needed. Leaders were also recognized (not self-appointed) and then disengaged when no longer needed."[11]

Further analysis is given by Sprout Distro:

In The People of the Three Fires: The Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan author James A. Clifton explains how Potawatomi society was structured with regard to its decision-making. What he outlines is a structure that bears many similarities to what anarchists desire: a society based on networked groups (in this case villages) that make decisions using consensus. Clifton writes:

“…public councils and consensus-seeking public debate were regularly conducted locally, on a smaller scale, about matters affecting the local community, not the tribe as a whole. Important decisions affecting kin groups and villages, just like those involving the whole tribe, had to be thrashed out in public forums open to all. Since such decisions were arrived at by consensus rather than by majority vote, there was little room left for dispute or frustration among a minority on any issue. The emphasis on public debate, on consensus, and on the sharing and decentralization of political power reflects the great value the Potawatomi placed on equality in both the political decision-making process and the distribution of economic resources.”

Clifton also discusses a council of all Potawatomi villages that took place in 1668 and uses it to explain how decisions were made. The Wkamek (leaders/representatives) gathered together to discuss the issue (in this a trade dispute with the French). Sitting immediately behind each individual Wkama were the kinsfolk they represented who were there to check in on the Wkamek behavior to assure that their actions and statements reflected the villages’ desires. The decision that was reached was the product of consensus and was accepted by everyone.

When solving internal disputes, the Potawatomi’s practice was similar to what many anarchists talk about when they speak of voluntary association. Rather than require unanimity and conformity, the Potawatomi understood that factions occasionally did form. The solution wasn’t to chastise members who held different opinions; rather they were encouraged to split off from the community and settle elsewhere and establish their own villages.[12]

Economy

Custom said that individuals "could only take as much as they needed, that they must share everything, following Nishnaabeg redistribution of wealth customs, and no part of the animal could be wasted."[13]

Environment

Nishnaabeg custom says that when making a decision, a community must consider its impact on plants and animals and on the next seven generations of humans.[14]

The precolonial Nishnaabeg made treaties with surrounding animal nations. For example, they agreed with the fish nations that humans would only fish at certain times of the year and at certain places. They would only catch as much as they needed to eat. Treaties with other animal nations said that humans would preserve forests and that human hunters will not let meat go to waste. A general agreement with the animal nations formed, according to tradition, a time long ago after animals left the territory in protest of humans wasting meat and disrespecting animals. The animal nations formed a council and the chief deer put forth a request to the Nishaabeg, "Honour and respect our lives and our beings, in life and in death. Cease doing what offends our spirits. Do not waste our flesh. Preserve fields and forests for our homes." The Nishnabeeg agreed, and the animals returned to the land.[15]

Neighboring Societies

In precolonial times, the Nishnabeeg signed a treaty with the Haudenosaunee called Gdoo-naaganinaa, meaning "Our dish." The treaty recognized the fact that the two parties ate from a shared "dish" since they shared hunting areas and overlapping plant and animal species depended on the health of both parties' lands. The treaty said that neither party could abuse the landbase, and Nishnabeeg and Haudennosaunne delegates were required to regularly gather for meetings and rituals.[16]

- ↑ Leanne Simpson, "Looking after Gdoo-naaganinaa: Precolonial Nishnaabeg Diplomatic and Treaty Relationships" in Native Historians Write Back: Decolonizing American Indian History ed. Susan A. Miller and James Riding In (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 2011), 242n.

- ↑ Simpson, "Looking after Gdoo-naaganinaa," 96.

- ↑ Leanne Simpson, "Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation," Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 33, no. 3 (2014), 2-6. https://decolonization.org/index.php/des/article/view/22170.

- ↑ Simpson, "Land as pedagogy," 11.

- ↑ Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 3.

- ↑ Simpson, As We Have Always Done, 128.

- ↑ Simpson, As We Have Always Done, 131.

- ↑ Robin Wall Kimmerer, "The Serviceberry: An Economy of Abundance," Emergence Magazine, 2020, https://emergencemagazine.org/story/the-serviceberry/.

- ↑ Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of Plants (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013), 54-55.

- ↑ Simpson, As We Have Always Done, 4.

- ↑ Simson, As We Have Always Done, 3.

- ↑ https://www.sproutdistro.com/2011/10/07/indigenous-forms-of-consensus/.

- ↑ Simpson, "Looking after Gdoo-naaganinaa," 100.

- ↑ Simpson, "Looking after Gdoo-naaganinaa," 100.

- ↑ Simpson, "Looking after Gdoo-naaganinaa," 97-98.

- ↑ Simpson, "Looking after Gdoo-naaganinaa," 100.